‘At all times, my primary focus, and that of my predecessors, has been to ensure patient safety. I have also made it clear that I will be guided in my decisions by the available evidence’

That was Simon Hamilton, Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) Health Minister in the Northern Ireland Executive, talking last week about Ireland’s lifetime ban on gay blood donation.

Here’s the thing: what would happen if Hamilton applied this principle to NI’s drugs policy? What would happen if we had a national conversation about reforming our drug laws, spearheaded by the Minister of Health and foregrounded in the Northern Ireland Assembly? A rational debate, based on scientific evidence, and rooted in social justice?

This was the question posed by some people at the end of a conference on paramilitary violence in Northern Ireland and community responses to it on Saturday 5 December in the Institute of Irish Studies at Queens University, Belfast.

A spokesperson for the Cannabis is Safer than Alcohol Northern Ireland (CISTA NI) political party asked during the final open session of the conference ‘Why is Northern Ireland alone in not having such a debate’.

John Lindsay, an anti-vigilantism researcher from Derry outlined in his talk, Republican Action Against Drugs (RAAD) — Portrait of a terror gang and popular protests again them, brutal paramilitary ‘justice’ has persisted and even increased in ferocity in spite of ceasefires by the main paramilitary groups.

‘RAAD Not in Our Name continue to monitor and campaign against paramilitary threats and violence.‘I hope that the lessons learnt from the campaign against RAAD can help inform the ongoing struggle to end the menace of paramilitary intimidation and violence within our communities.’ Paramilitaries, he said ‘now police drug use and dealing’.

Local people in Derry took a stand against RAAD – re-naming them ‘Real Attack Against Democracy’ – and took to the streets in protest.

Resource centers set up to mediate between people and paramilitaries ended up facilitating violence. Back in the seventies, Lou Reed was talking about a drug deal when he wrote ‘I’m Waiting for My Man’. If he had been writing in Derry today, he would have been talking about RAAD, who arranged ‘punishment’ shootings ‘by appointment.’

Shootings still happen by appointment with some dissident republican groups – and paramilitaries continue to control the drugs trade in their own areas. New Belfast based group Action Against Drugs (AAD) are ‘just people who rob drug dealers and/or rid competition under the disguise of republicanism.’

Professor Liam Kennedy, a historian and author of ‘They Shoot Children, Don’t they?’ told the conference ‘It’s been nearly fifty years since the troubles started: Kneecappings, beatings and intimidation are forms of torture, on a vast scale. Over that half a century’, he pointed out, ‘there have been more than 6,000 recorded instances of paramilitary ‘punishments’.

The conference, co-hosted by Professor Kennedy and Irene Boada of the Institute of Irish Studies at Queens University last Saturday 5 December, was packed when I arrived. I was late. Ironically, I had just come from an Amnesty International NI event to take part in a campaign to support victims of violence. As I walked up the stairs, newly elected Irish Labour Senator Mairia Cahill, was telling of her personal experience of intimidation by the IRA:

‘The conversations today have been important,’ she said. ‘In relation to civic responsibility is the fact you have disengagement with the political process and that creates a vacuum. ‘There is no place for criminality on any side within any of these working class areas. It perpetuates a cycle of violence and in many instances that cycle ends up in the home.’

Senator Cahill had told an award winning BBC Northern Ireland Spotlight programme that she had been raped by a senior west Belfast IRA figure in 1997 – well after the two IRA ceasefires – when she was 16. Rather than allow her to report the alleged rape to the police, leading IRA and Sinn Féin figures tried to hold their own internal inquiry into her claims. She said that the republican leadership was more interested in protecting its reputation than in obtaining justice for her.

While the majority of beatings, intimidations and mutilations of women have traditionally been small compared to those for men during the troubles, they are far from negligible. The very first attack on a woman in the recent troubles was carried out by the IRA on a young woman from Derry, Marta Doherty, who had become romantically involved with a British soldier.

Women may only have been around 4% of ‘punishment’ beatings and around 9% of the 3500 killed during the troubles, but there is a sense in which women have experienced the trauma associated with the troubles to a far greater extent than official figures might suggest. Bernadette O’Rawe from West Belfast articulated this trauma when she spoke of her personal involvement in Northern Irish communities: ‘There is a blind eye turned to ‘punishment’ beatings – they should be called simply beatings. Referring to them as ‘punishments’ confers legitimacy. Nowhere else in Western Europe is there such a thing as kneecapping [shooting bullets into a person’s knees]… That is nothing more or less than child abuse.’

The last speaker, PSNI Chief Inspector Tim Mairs had just stepped down from addressing the final session when a wiry middle aged man ran up, shaking, to the front of the room.

‘Twenty years ago’ he said, ‘I was the victim of a paramilitary attack. They broke my arms, they broke my legs, I’m still suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. I felt nothing, I was numb. Except for what was going on in my head.’ His contribution – unplanned and unscripted, terrified of speaking in public for the very first time – was the emotional and dramatic highpoint of the conference. It came from the heart, from bitter experience. The leader of the gang, he believes, was a senior IRA man, still prominent today.

The conference had posed the question: How widespread are the problems of paramilitary violence and intimidation within Northern Ireland? What is the effect on individuals, families, neighbourhoods and communities? Are children especially vulnerable?

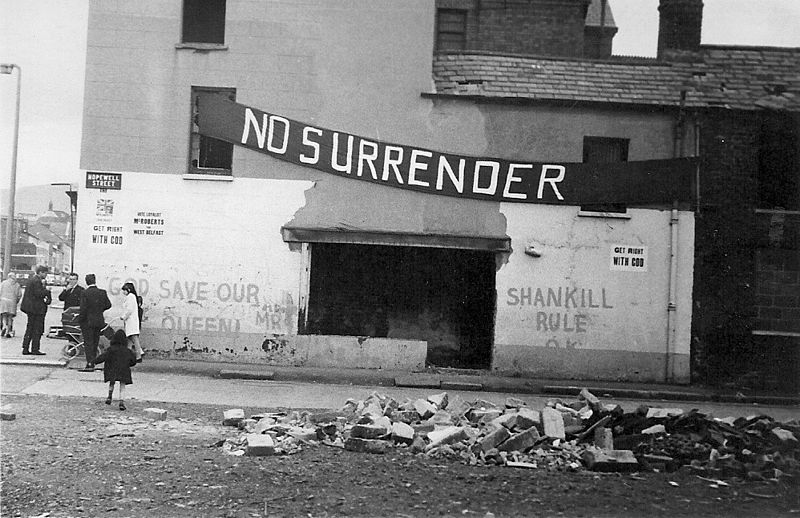

Paramilitaries, as Ulster Unionist Dr Chris McGimpsey, a UUP councillor with a lengthy involvement in community action, pointed out in his address ‘Young, Loyalist and Threatened’, have ‘effectively lost their rationale – because in loyalist areas they should be disappearing. But they are clearly not, which means there must be more than the standard public rationale they give for existing. We have to persuade them to disband.’

McGimpsey pointed out that young people are traumatized and re-traumatized with stigma and ‘punishments’ while paramilitaries boast of the level of control they have in local areas. Quoting the example of the notorious loyalist Johnny ‘Mad Dog’ Adair, he told how the Belfast flat from which Adair dealt drugs had been exposed by NI paper, Sunday World. Closed temporarily, Adair swiftly reopened the flat, with graffiti painted outside it: ‘Open for Business as reported in Sunday World’. ‘They are para mafias’ said McGimpsey, who worked with former paramilitaries to secure the loyalist ceasefire.

Like me, Chris had visited the anti-mafia museum in the Sicilian village of Corleone, from which Mario Puzo had taken the name of the fictitious Sicilian Mafia family who settled in New York, The Godfather. In Corleone’s International Documentary Center of the Mafia and the Anti-Mafia Movement (CIDMA) you can wander through a room of images of mafia victims by photographer Letizia Battaglia.

Like the images of paramilitary victims in Northern Ireland, the photographs show the propaganda value common to both Mafia and para-mafia paramilitary groups. Like the images of paramilitary victims, shrouded in black bin bags, dumped in ditches along the border. Like Battaglia’s image of a Mafia victim, his mutilated body posed by his killers in a makeshift coffin they dumped in a back street, such images are designed to rob the community of agency and dehumanize the victims.

Liam Kennedy finds it difficult to get his head around ‘the willingness, sometimes the enthusiasm of volunteers to involve themselves in paramilitary-administered “punishments” such as kneecapping and severe beatings: In effect, they are forms of torture on a vast scale,’ he said. “One thing is for sure, there will be no great ballads written about the brave volunteers whose normal duties include brutalising members of their own community, be they from loyalist or republican backgrounds’.

Kathryn Johnston is a freelance journalist and researcher based in NI, and Womens Officer for the Labour Party in Northern Ireland