This article was originally published on The Influence.

A few hours before the media announced Prince’s death on April 22, I sadly read the news of yet another professional wrestler passing away to a suspected overdose, at the age of 46. On any other day, Chyna —real name Joanie Laurer—would have received suitable media inches. Her legacy will forever be culturally underrated.

In the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, Chyna reflected social changes and became the first woman to compete with men—in every sense—in her field. She won titles such as the WWE Women’s Championship, competed in the Royal Rumble and King of the Ring tournament, and most notably was a two-time Intercontinental Champion. She flexed her muscles when it came to earning power, and she was rightly accepted as a bona fide superstar. She later branched into glamor modeling and adult entertainment too. She was undoubtedly a pioneer.

For those of us who follow her sport—or “sports entertainment,” as some would have us call it—the feeling of losing yet another top name at such an early age was far too familiar. The list of wrestlers who departed too soon would make for some lineup. Legends such as Rick Rude, Road Warrior Hawk and Mr Perfect Curt Hennig were icons of the ’80s and ’90s “excess” era—a time where wrestlers often relied on substance use just to make a pay day. All had a cause of death linked to drugs, life on the road and an array of clandestine complications

Default intellectual snobbery can kick in when it comes to professional wrestling. It’s easy to mock the flamboyance and theatricality which stitch the industry together. But beneath the sheen and glamor, there’s a cold stream of realism that travels alongside the wrestlers as they circle the globe, struggling to make their lives fit into the squared circle.

I found myself on the hook of wrestling from an early age, lured by the shimmer of larger-than-life characters capable of eliciting reactions of pure horror, joy, fandom and intrigue. There is perhaps no rawer form of entertainment. The gladiatorial metaphor is overused, but it does perhaps make the best case for describing the emotions which wrestlers can create, if one is willing to go along for the ride.

To find out more about wrestling’s issues with drugs and lifestyle, I spoke with Jim Smallman. He’s a podcast host on Acast and the Distraction Pieces Network’s Tuesday Night Jaw; he also co-owns Progress Wrestling, which has become one of the most respected companies on the global independent circuit. Like all of us, he has witnessed many admired wrestlers pass away.

You only have to read a couple of wrestlers’ autobiographies to know how dodgy the lifestyle was for wrestlers in the past, working in a different town every night at least six days a week, plus TV tapings, plus needing to work out, stay awake, get to sleep… and so on,” Smallman tells me. “One reason that so many wrestlers I watched when I was a kid are now dead is the lifestyle. There have been a lot of accidental overdoses from wrestlers—thankfully less so in recent years; in the late 1990s there seemed to be far too many—who are lonely in a hotel room in the middle of nowhere and take one too many painkillers just to help them sleep and get through the night.

The principle finding of Bruce Alexander’s famous Rat Park experiment was that rats were susceptible to their environment when it came to substance management. Healthy, happy rats did not choose to self-administer the substances on offer, whereas rats in emotional isolation did turn to drugs.

To hear the descriptions of insiders like Smallman, the wrestling industry of the ‘80s and ‘90s could be comparable to this addiction experiment.

“You’d have guys who were injecting massive amounts of steroids, then doing cocaine before matches, then smoking weed, taking muscle relaxers or painkillers in large amounts for recreational reasons, and drinking,” Smallman says. “It’s no wonder we’ve lost a lot of guys in their early 40s.”

“These days,” he continues, “there is a new generation of performers who are ‘straight edge,’ something that would not have happened in the 1980s and 1990s. Nutrition, exercise and training seem much more important than partying—not that it’s gone completely.”

Perhaps the high-profile deaths have played a grim part in winning professional wrestling more respect in recent years. The cries of “fake” and the mockery which professional wrestling used to attract have widely been replaced by a new appreciation for the performers’ prowess and the brutal physical demands of their profession.

Every time you take a bump on your back in the ring, you may know how to fall if you’re trained, but it’s the equivalent of being hit by a car at 20mph,” Jim Smallman tells me. “Imagine having that impact on your knees, back, and neck—ten times a night, every night. Then you have to get into a rental car and drive a few hundred miles, sleep in a motel room or sit on a plane and do it all again. Physically, it’s a really tough job. I’ve never met a wrestler over the age of 40 who doesn’t have some genuine health problems or has never had serious surgery

Like any contact sport, the wrestling industry has had to address the problems that sometimes occur with prescribed pain relief. When your ability to keep your pain under control dictates your salary, it soon becomes apparent why so many in the industry have relied upon pharmacological help. And when high and/or regular dosages are combined with isolation and other stressors—as well as combinations of different drugs (Chyna was reportedly taking medication for anxiety and insomnia)—it can be a recipe for severe problems and dangers.

Other sporting industries, such as the NFL, are slowly creating a dialogue around harm reduction practices. Education about healthier lifestyles and safer drug use, as well as practical measures like naloxone distribution, are key.

A number of former NFL players, such as Eugene Monroe, Kyle Turley, Derrick Morgan and Jim McMahon have also come forward with their personal testimony as to how medical marijuana helps minimise the potential harms of other forms of pain management. Prominent marijuana researchers such as Dr Lester Grinspoon have also backed the calls to allow cannabis in sports—and there have been early indications that cannabis could be beneficial for concussions.

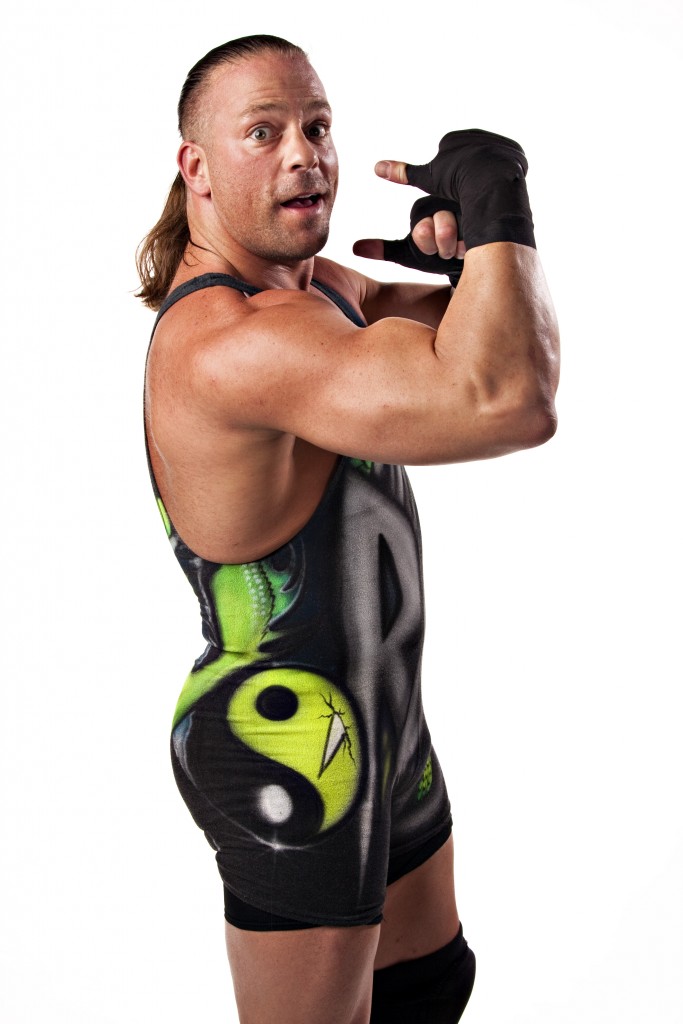

While the conversation around using medical marijuana in sports is still in its infancy, some in the wrestling industry have long championed such reform moves. Rob Van Dam is an actor and professional wrestler who’s won a total of 21 titles in numerous federations. Like many top athletes, such as Usain Bolt and Michael Phelps, Van Dam has been open about his advocacy of marijuana in athletic pursuits.

But will big league wrestling promotions ever accept medical marijuana?

The current federal position on marijuana is why the big companies ban the usage,” Van Dam tells me, “but I’ve already seen wrestling shows where everyone is using. If the NFL convinces sponsors that using THC/CBD to protect the brain from trauma is a good idea, WWE will surely follow suit.

Optimistically, he says of my question: “To say ‘ever’ gives me a lot of room to say, yes.”

The WWE now has what it calls a “wellness policy”—a program designed to test and support current and former stars who may have substance use issues. This is welcome. But federal law still rules out making marijuana one of the available harm reduction options.

Because the federal government says that marijuana has ‘no proven medicinal benefits,’ the standard setters of the wrestling industry don’t allow it,” Van Dam explains. Indeed, “the WWE fines wrestlers who test positive for marijuana and will take disciplinary action if positive results persist.

With cannabis use still punishable inside and outside the wrestling industry, there seems to be little appetite to address the more nuanced question of allowing wrestlers to consume cannabis for therapeutic purposes.

But would more wrestlers swap from pharmaceutical drugs to medical marijuana if it was allowed?

If people were educated on the safety risks of pills versus marijuana at an impactful age, we’d see many athletes and non-athletes choose to use the healthier alternative,” Van Dam tells me. “Some people would do both. Many would choose not to—especially those who are concerned with fitness like a pro athlete.

Professional wrestling provides a case study for when society and individuals push on, ignoring the warning signs, and preventing an open conversation on drug-related problems.

In contrast, an open dialogue around drugs would be the only way to truly address the core issues which should concern us: how we can save lives; how can we protect people from potential substance traps; and how we best support those who most need it. We’re all products of our environment, and professional wrestling exemplifies this.

Despite Chyna’s tragic death this year, sane voices like that of Rob Van Dam mean wrestling fans can hope to see the end of an era where some of the brightest stars fade far too early. As in wider society, this isn’t about the drugs themselves. It’s about the situations that lead people to potential harms—and finding practical, non-dogmatic ways to mitigate them.

Jason Reed is a writer, film producer and host of the podcast Stop and Search. He is the Executive Director for LEAP UK. You can follow him on Twitter: @JasonTron.