Introduction

In the 1990s, Iceland was far from excelling in its prevention of drug use by young people. In fact, annual data collated by the Icelandic Government suggested that the situation was getting worse.

From 1992 to 1998, the proportion of 15 to 16-year-olds who smoked cigarettes on a daily basis in Iceland increased from 15% to 23% and those who smoked hash from 7% to 17%.1 Alcohol use among this age group also fared poorly in comparison to the rest of Europe, with 21% having been drunk 10 times or more in the past 12 months. With regards to consumption, 40% of respondents stated that they had been drunk in the past month and 25% said they were smoking cigarettes every day.2 Alongside this increase in use, the percentage of 15 to 16-year- olds who reported having had an accident or injury related to alcohol was 14%, second to the UK at 17%3.

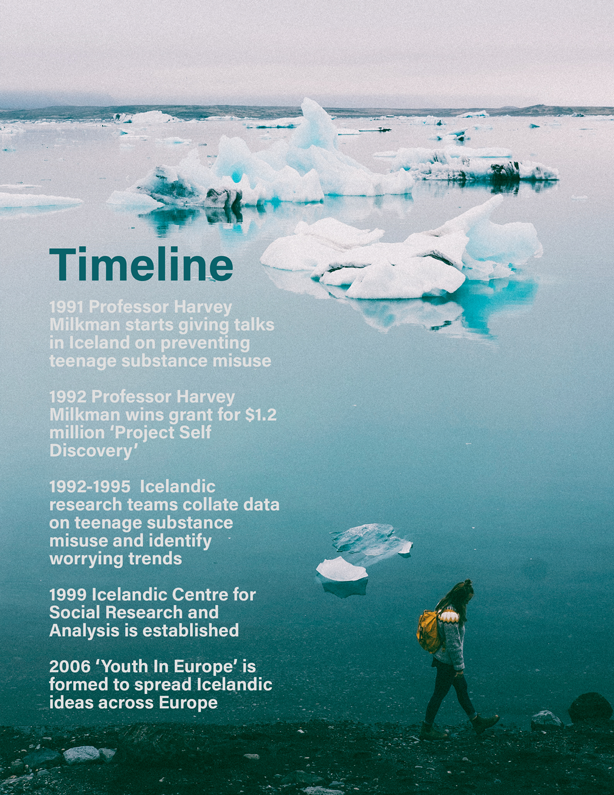

The Government, parents and schools across Iceland became increasingly concerned as problematic use increased. To examine why this was happening, in 1999, the Icelandic Centre for Social Research was formed, a non-profit research institute based in Reykjavik. The centre immediately started collaborating with policy makers and practitioners in the field, with the goal of better understanding the societal factors influencing substance use among young people and to develop robust interventions around prevention.4

The ideas formulated by the centre drew heavily from work undertaken in the United States by American Psychology Professor Harvey Milkman. In 1992, Milkman won a grant of $1.2 million for ‘Project Self Discovery’, the aim of which would be to help educate teenagers about ‘natural highs’ as a means of turning them away from drug use and crime.5 The concept was to teach young people aged 14 and over new skills and give them positive experiences which would produce a natural ‘high’. Alongside new skills, the young people were given quality life education, teaching them how to manage their thoughts, feelings and interactions with people.

By 2006, the annual data collated from young people in Iceland as part of the project was so convincing that it led to the formulation of ‘Youth In Europe’, an organisation set up to spread the Icelandic prevention model further afield. To date, the model is now applied in 35municipals (the model is not delivered through Iceland’s central government), has analysed 99,000 questionnaires and helped to develop localised strategies to prevent teenage substance use around Europe.