The Netherlands and in particular Amsterdam, has always been famous for its coffeeshops. Not for the amazing latte’s and cappuccino’s they serve, but for weed, hash and other cannabis related products. A not very well known fact, however, is that cannabis is actually not legal in the Netherlands. But with the introduction of the ‘controlled cannabis supply chain experiment’, that might actually change.

The current policy is quite complicated. Coffeeshops are allowed to sell cannabis because it is tolerated by the Dutch government, however there are certain rules they need to follow. Coffeeshops are not allowed to have more than 500 grams in their possession, they can sell a maximum of 5 grams per person per day, they cannot sell to minors and they cannot serve alcohol. Supplying coffeeshops with cannabis is actually illegal, so this is being done through a complicated ‘back-door’ policy. So in short: they are allowed to sell, but not allowed to purchase.

There might be a change coming with the start of the ‘controlled cannabis supply chain experiment’. Ten municipalities with a grand total of 79 coffeeshops have been selected for the experiment. These coffeeshops will start selling legally produced cannabis supplied by ten government-designated growers. The aim, according to the Dutch government’s website, is to find out whether it is possible to regulate a quality-controlled supply of cannabis to coffeeshops and to see if the experiment has any effect on crime, safety and public health. A lot of people are happy about the new direction the Netherlands seems to be moving in, but others are critical and think progress is too slow, seeing as other countries and states have already legalised. The experiment is set to take place in 2021.

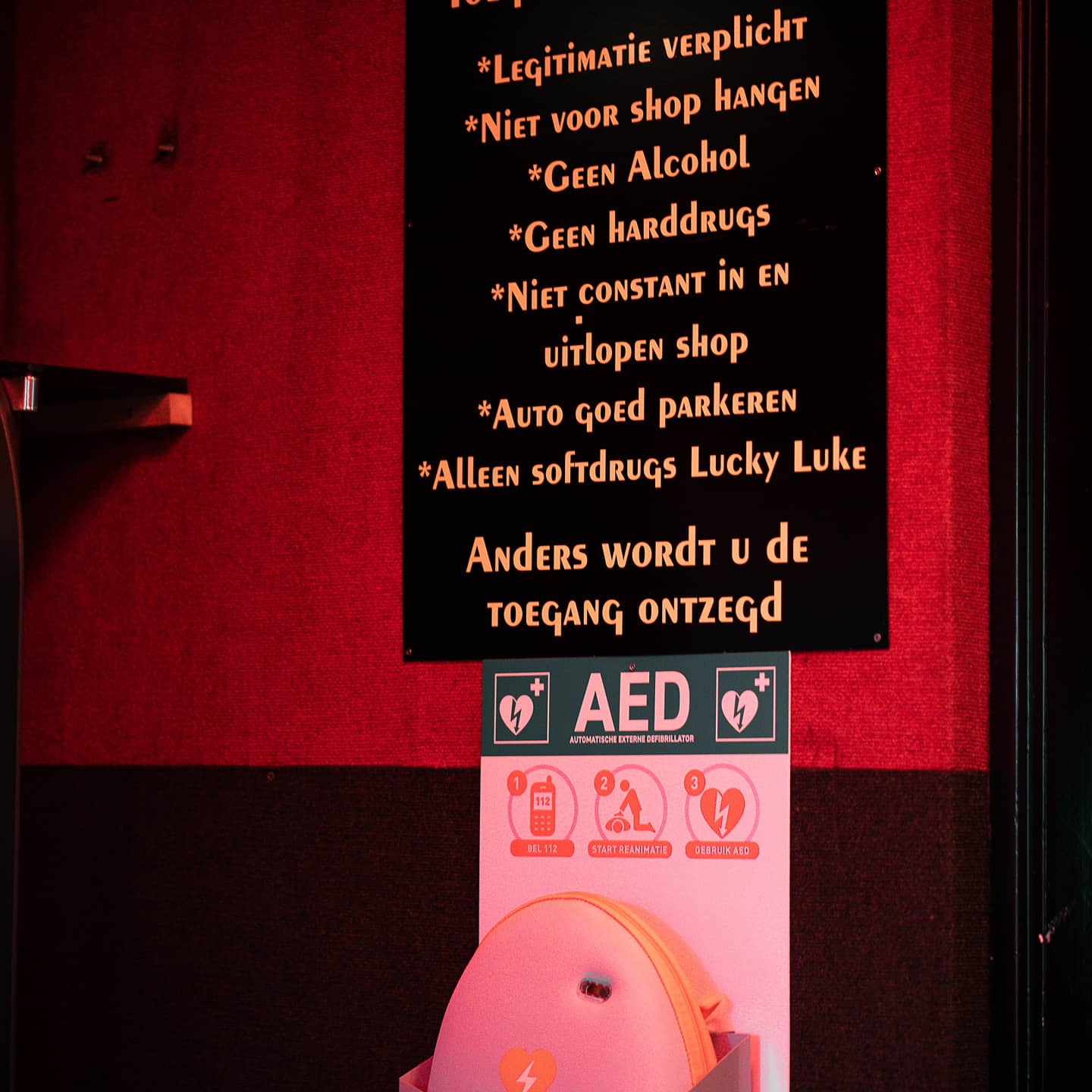

A set of rules posted on a wall in an Arnhem coffeshop, original from Gerrit Driessen

First there will be a transitional period that will last six weeks. In that time, coffeeshops can still decide whether or not they want to buy from the official growers, their own sources or a bit of both. After a month and a half they are required to buy their product from the ten appointed growers, it’s up to them which grower(s) they decide on.

Although there is not much known about the ten growers-to-be, there is one group that has come forward about their cultivating ambitions: Project C. The trio consists of a GP, a lawyer and a politician. Not necessarily the first people you’d think of to start a business growing cannabis. Joep van Meel, the politician, explains. “It all started with an idea that Peter [Schouten, the lawyer] had, he brought us together and we agreed with him that there needs to be a change in current backdoor policy. It’s great that the government is doing this, but the experiment has to succeed. If it fails, this discussion will be off the table for the next thirty years.” So the three got to work on a manifesto, a declaration of their policy and aims. With three completely different backgrounds, van Meel thinks they can tackle the issue from different perspectives. “Ronald [Roothans, GP] has seen cannabis-related problems in his medical practice, but also patients that use it for pain. Peter, as a lawyer, sees the criminal law side of things: people that lose their home or are being threatened by gangs. As for me, having been active in politics for a while, I think it’s time for a change because we have a drug-policy that isn’t based on scientific research.”

The National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) in the Netherlands published a ranking of 19 different kinds of ‘drugs’ (including alcohol and tobacco) in 2009 based on toxicity, potential for dependency and social harm. After heroin and crack, tobacco and alcohol grace the third and fourth place. Cannabis is in 12th place. “Not far beneath heroin and crack, we can see alcohol on the list, which is being sold in supermarkets. We even advertise for it on television… And then all the way down the list is cannabis. That kind of ambiguous policy bothers me,” explains Van Meel.

But what is the motivation behind the plan? Are they hoping to make a lot of money or are they in it for the reform? Van Meel explains: “Our first and foremost motivation is our ideal, we think the current policy is ridiculous. I smoke a joint from time to time and I think that the stigmatisation of cannabis users is very disappointing. At the end of the day it’s still a business, so of course we’re hoping to make some money out of it, but at the same time we’re planning on spending 30% of our net profit on research and addiction care.”

A set of cartoon cowboys hold their middle fingers up, original from Gerrit Driessen

So how do coffeeshop-owners feel about the experiment? Especially when considering that they didn’t really have a say in whether or not their municipality would enter in the experiment. Jill Poppinghaus owns coffeeshop Lucky Luke in Arnhem. “We as a coffeeshop are feeling very good about the experiment. Because of the backdoor policy, we are not a 100% legal. We pay taxes like we’re legal, but apart from that we have no rights. I hope that with the experiment we can move in a direction of legalisation so that we can have the same rights as any business in the Netherlands. People need to realise that we are just a shop, just like a bakery or a butchers. The only difference is that we sell something that people might not be used to. If I see who walks in to my shop on a daily basis, I can’t imagine that there’s still people who think that it’s only criminals or junkies that come in. It’s all sorts, from lawyers and schoolteachers to off-duty police officers.”

Are there any downsides to the experiment for the coffeeshops? According to Poppinghaus, there are. “We didn’t have a say in participating, but we are expected to invest a lot of money: a new safe, a new payment system, we need a new security system for the weekly stash that comes in… These are all at our own expense.” Another problem the coffeeshops might be facing is the supply of hash. “To make a kilo of hash, you need a hundred kilos of weed. Right now most of the hash we sell in the Netherlands comes from Morocco, but I don’t think the Dutch growers will be able to grow and produce enough hash for all the coffeeshops in the experiment.” This might form a problem, because according to the 2019 National Drug Monitor by the Netherlands Institute for Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos), 30% of people that visited a coffeeshop in the previous month preferred hash over weed.

But is this experiment going to be the best way to move towards legalisation? Not according to Rick Brand, owner of De Baron in Breda coffeeshop. “If you want to legalise cannabis in a way that this plant deserves, it needs to be removed from the list of prohibited substances. Nowadays it’s being legalised with piles of legislations and regulations, different in every country, state, region or city. It’s unnecessary, it needs to just be taken off the list, it’s as simple as that.”

Still Brand is happy to be in the experiment and glad that he will be able to offer his customers a clean product. “The experiment is a step in the direction of legalisation. The backdoor policy will end, which is good, although it didn’t bother me all that much, because there is such a wide range to choose from. The only problem is that I can’t guarantee the quality. I can tell my customers that I put it under a microscope and I can test my product, but I’m like a food taster from ancient Egypt, putting myself at risk to see if a product is any good. We don’t know what happens when you smoke weed with pesticides, we have no idea what kind of damage that does, so in that aspect I’d be very happy with regulation and certified growers to make sure we get a clean product.”

A good example of the popularity of the coffeeshops in the Netherlands happened on the first day of lockdown. On the 15th of March at 5PM the prime minister announced in a press conference that all restaurants, bars and coffeeshops were closing down an hour later. At around 5.30 huge queues formed at coffeeshops all over the country, pictures of the lines were widely shared on social media and news platforms. A video arose of two guys handing out cards with their phone number to people standing in line. To stop the black market from taking over, coffeeshops were allowed to open up again the next day, as long as they made sure they had a takeaway function.

A cannabis and soft drink menu hangs in an Arnhem coffeeshop, original from Gerrit Driessen

There’s still quite a few challenges ahead, according to Brand. “Ten growers is not enough. If there’s only ten growers and all ten are doing badly, people will go back to the black market. There is also a possibility that in the first 6 months the growers might run into some start-up problems. I expect about three growers to do it right from the start. But imagine if all 79 coffeeshops want to purchase from these three because the others don’t have good quality products… I’ll have to close my doors at 3PM every day, because I’ll be sold out in no time.”

Brand isn’t the only one to express his concerns. James Burton, who was one of the first government-designated medical marijuana growers in the Netherlands, doubts if the experiment will be a success. He thinks the same thing will happen that did back in 2003 when he was growing: the price will be too high and the variety too low. If either one of those factors is off, customers might buy their product elsewhere, either in coffeeshops that are not in the experiment or on the black market. Back in 2004 the rise in price of medical cannabis led the Dutch government to destroy kilos of excess cannabis at the waste processing facility in Rotterdam, while customers went back to buying their medicine from coffeeshops instead of pharmacies.

One question remains, however… Is this experiment the best way to move towards legalisation? The Netherlands used to be at the forefront of drug-policy reform with the first coffeeshops dating all the way back to the seventies. But with Canada, Uruguay and a number of states in the USA going for full legalisation, it seems that now we are falling behind while other countries are developing. Is a four year long try-out with government-designated growers really what the Netherlands needs before possibly moving onto legalisation? “We’re only slowly moving towards legalisation now, whereas we used to be one of the most forward thinking countries when it came to drugs. It’s a shame,” says Poppinghaus.

Lara Smit is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at contactlarasmit@gmail.com