VolteFace invited David Cameron’s former Director of Policy, Paul Kirby, to submit a piece on the subject of prison reform. What follows is a magnum opus…

There’s no shortage of people worrying about the world running out of things.

Oil, water, food, antibiotics, polar ice – they all have people worried. But no-one seems to be worrying about the shortage of something that’s essential to social justice.

We are running out of punishments.

As societies become more civilised, they find punishing other humans less and less attractive. This is a new problem. For most of their history, humans have been disturbingly inventive in devising punishments for rule-breakers. People have been burned, hung-drawn-and-quartered, flogged, enslaved, exiled, relieved of their fingers, branded, transported, stoned, had their heads shaved, been tarred-and-feathered and put in the stocks – to name just a few.

Most punishments have been physical ones – death, mutilation or beating. In Western Europe, we often forget that most people in the world (over 60%) live in countries which still use the death penalty. But most of them don’t use it very often. Perhaps surprisingly, fewer countries still use corporal punishment – only 33 countries, a mix of Islamic countries or former British colonies which kept the British tradition of flogging.

A prison modelled after Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon (Source: Flickr – Paolo Trabattoni)

As countries have abandoned, or at least reduced their use of, physical punishment, they have tended to fall back on imprisonment as the only remaining “serious” punishment. In many Western countries, unless a convicted offender is sent to prison they are seen by much of the public (and the media) as having “got off with it”. A UK poll showed that 80% of the public and 90% of the police thought non-custodial sentences were “soft punishment”. Whilst many of the public said prison didn’t work, two-thirds of them thought that was because sentences were too short and prison life too lenient.

The punitive alternatives to prison are not obvious. Serious financial penalties are hard to impose on poor people, so they aren’t. And most people in prison are poor people. US data shows that, before going to prison, prisoners had only 50% of the median income of their ethnic and age group, e.g. young hispanics in prison had only half the income of other young hispanics. Many fines are not repaid. The UK Government, for example, has written off hundreds of millions of pounds of fines in recent years.

The penalty for not paying a fine, of course, is to go to prison. But imprisonment has its opponents too. We know what most offenders need to avoid re-offending: a home, a job, a loving relationship, self-esteem and a positive peer group. We also know that the biggest threat to all these is being sent to prison. Indeed, that is the explicit point of prison – to remove what people most value in the world.

It feels as though the West is at a turning point in its use of prison.

The US is considering big cuts to mandatory sentences. Europe is struggling to afford it’s prison population. The UK and others are recognising that prison isn’t the right solution for many prisoners such as the seriously mentally ill. But if we stop imprisoning people, what punishments will we have left for serious crime or where offenders don’t respond to other punishments or interventions? Yes, justice is about rehabilitation and restoration. Prison does seem a bad route to these goals for too many offenders.

But justice is also about retribution, deterrence and incapacitation. Only prison currently seems to deliver for the public on those goals. (Anyone who doubts this should look at the Netherlands where liberal sentencing has led to empty jails but politicians who are unwilling to be seen closing prisons. Instead, the Dutch are housing Belgian and Norwegian prisoners to fill their prisons.) So, if it’s all we’ve got left, will prison be the last of the brutal punishments to survive and how could it evolve?

Interior. Halden Prison, Norway – ‘the worlds most humane prison’ (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

It’s tempting to think that imprisonment has been used as a punishment, like capital and corporal punishment, for thousands of years. But that’s not true.

It’s a fairly modern invention and has changed in nature hugely since it was introduced. Before the 17th century, a prison was used simply to hold people pending a trial or a punishment. It was not a punishment in itself. In fact, modern prisons were a cuckoo that took over a different nest.

The first modern prison is usually seen to the London Bridewell. But this was initially a house of corrections for the poor, vagrant and homeless, aiming to take them off the streets and instil a work ethic into them. This side of it was widely replicated as “Workhouses”. But the idea got taken over by prisons. It was the public reaction in England against death sentences in the late 18th century that led to the growth of prison, hard labour and transportation as common sentences. At its peak in 1800, there were 220 offences that could earn a death sentence in an English court, most of them trivial. Juries would sometimes refuse to find someone guilty of minor theft or poaching to avoid the sentence. Even if issued, death sentences were mostly commuted – only 7,000 out of 35,000 English death sentences between 1770 and 1830 were carried out.

As the use of prison grew, there was growing Western social science and philosophy about the best sort of regimes to optimise punishment and rehabilitation. For much of the 19th century, this often meant separation of all prisoners (effectively solitary confinement), silence and continuous hard labour. It was taken for granted that prisoners would be beaten whilst in prison.

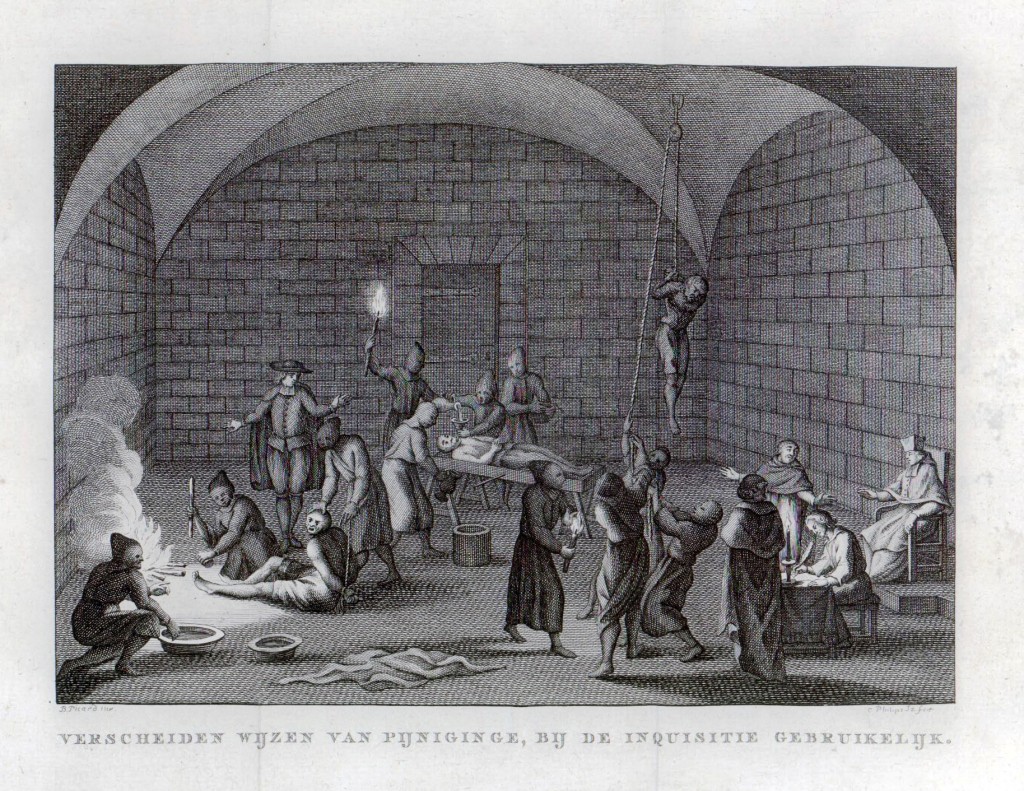

An artists rendering of a 17th century Spanish Inquisition torture chamber (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Read our Editor-in-Chief on the need for a new conversation about prison reform here

In the US, for example, late 19th century prisons tortured prisoners with a water coffin, iron cages on their heads and frequent use of the lash and paddle. Flogging in prisons has disappeared only fairly recently, e.g 1962 in the UK and 1972 in the US. Most Western prison regimes are now pretty similar. What varies enormously is the proportion of the population who are imprisoned. The US has increased its state and federal prison population from 320,000 in 1980 to 1,560,000 at the end of 2014 – a 380% growth. If we add in, the 700,000 in local jails and detention centres, there are 2.3m Americans in prison. Per head of population, the US imprisons 10 times more people than Germany or Denmark. The UK and Australia have pretty big prison populations, with an imprisonment rate roughly double that of the Scandinavian countries.

The UK has doubled its prison population in the last 20 years. But the US has 20% of the world’s prison population, versus 5% of the world population. 7% of babies born today in the US will go to prison. There is a 70% chance that a black man born in 1975 who dropped out of school will spend time in prison and 1 in 3 black men will spend time in prison.

The US “experiment” offers us the chance to see whether prison works in terms of deterrence and rehabilitation. A major study of US prisoners released in 2005 followed their progress for 5 years to 2010. Unfortunately, the results are appalling. 3 out 4 prisoners were arrested within 5 years of their release – many within the first year of release. And 16% of the released prisoners comprised a full half of all arrests in the US in the next 5 years.

The data on “frequent fliers” in prison is depressing. In New York City, for example, the 800 most frequently jailed individuals between 2008-13 had 18,713 incarcerations. That’s 22 each. One person was jailed 66 times. 9 out of 10 offences were misdemeanours. Looking at the frequent fliers, 84% used crack/cocaine, 37% used heroin, 52% were homeless and 37% needed anti-psychotic drugs in prison. This picture is repeated in other Western countries.

In terms of rehabilitation, prison looks like a bad solution. But there are a lot of other potential benefits from depriving offenders of their liberty. It prevents them committing crimes whilst locked up. It can deny them access to harmful drugs. It can disrupt their social network. It can offer them a supervised opportunity to reflect on their offences, change their behaviour and plan for a better future. And it can satisfy society’s demand for retribution.

So whilst there are many other policy issues about prison (e.g. better early prevention of criminal behaviour; decriminalisation of drugs; etc), we need some new ways to use imprisonment that can be sold to, and involve, the public as credible and well-understood punishments.

This could include:

House Arrest

The question is partly ‘how we can simulate its benefits without sending people to prison?’. But it’s also ‘how we can satisfy the public’s desire for retribution and incapacitation?’.

The answer requires us to be tougher on removing the civil liberties of convicted offenders who are not sent to prison. For example, in prison, an offender loses all privacy and is under observation at all times, including, for example, when mixing with others, when in bed or even when using the toilet. If non-prison sentences could be this draconian in removing liberties, then a better alternative to prison could still be created, that still satisfies public desire for retribution and supervision.

The alternative should be just that – a better option for those who would otherwise be sent to prison, rather than a way of toughening-up existing non-custodial sentences. So, civil libertarians please note, whilst my alternative is draconian, it is much better than prison.

The Romanovs (2nd Dynasty to rule over Russia) under house arrest. 1917. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

There are already sentences that limit people’s liberty in the community – home detention in New Zealand and Italy, house arrest in the US, electronic tagging in the UK, curfew orders and drug testing in the US. But they lack a strong brand and the ingredients of the sentence are often random and unpredictable – undermining their purpose in satisfying the public’s demand for justice. In Canada, for example, the Government has eliminated ‘house arrest’ for many crimes in the last few years and insisted on prison.

Let’s consider a new formal sentence called “House Arrest”. Sentences would include a fixed package of the community sentences currently available to the courts in many countries, including curfews, electronic tags, bans on meeting certain people, drug and sobriety testing, unpaid work, etc. However, it could be extended to include other restrictions and intrusions to simulate prison. This might include having all rooms in the offender’s home monitored for images and sounds on webcams, censorship of communication or bans on using phones or computers. Again, simulating prison, the offender could be allowed a certain amount of time when they were not “banged up” in the home and where, under supervision, they are out allowed to exercise or work, whether paid or unpaid.

An example of such a sentence for a 12 month sentence of House Arrest for an unemployed single man might include a requirement to: be in his designated home for 21 hours per day, wear a GPS electronic tag, pass weekly blood tests for illegal drugs, avoid meeting or communicating with a list of specified people, have a webcam monitoring each room and achieve functional literacy. By contrast, a woman with young children might be sentenced to 24 months of House Arrest to include, for example: a requirement to be in the designated home for 16 hours per day, continue to do her job for 6 hours per day, as well as take children to and from school, etc. She might be required to wear not just a GPS tag, but also a sobriety tag and be required not to associate with certain people or visit a list of named places. Her ability to leave the house for 8 hours per day could be subject to her continuing to be employed, her children attending school and her successful completion of a drug addiction programme. Whilst in the house, she might also have to do unpaid work (e.g. online or telephone work) for a certain number of hours per week.

It’s important that House Arrest sentences are predictable and comes as a entire package. Sentencing guidelines should set out a clear tariff of what total package comes for which offence and when house arrest should be used rather than a custodial sentence.

Deferred sentences

The threat of going to prison is a big one. Clearly, it’s not a strong enough deterrent for everybody or no-one would commit crime.

However, there is a way to use it’s deterrence when it would be most effective. That is when someone has been convicted of a crime and sentenced to prison. At that moment, the hope of avoiding prison (e.g. not being caught, or winning in court, or a getting a non-custodial sentence) has disappeared. At this moment, a conditional sentence could be hugely powerful.

A court could say “In 12 months from today, you will go to prison for 2 years unless you meet certain criteria”.

These criteria could include, for example: having been employed continuously for a certain time, having clean drug tests, becoming functionally literate, paying maintenance for a child, sticking to a curfew order and successfully completing an accredited programme to reduce aggressive behaviour.

Being convicted of another crime during the conditional period would automatically initiate the custodial sentence. However, a deferred sentence is different to a suspended sentence. With the latter, if someone does something bad they go to prison. With a deferred sentence, someone goes to prison unless they do good. A range of US states (e.g. NY, Texas, Washington) use “deferred sentencing” where in exchange for a guilty plea they adjourn sentencing for a period. If during that period an offender meets the court’s requirements the case will be dismissed with no sentence and, in some States, no criminal record. If the court’s requirements are not met, the offender will be sentenced.

This approach could work well with many offenders. However, my deferred sentence (rather than sentencing) is tougher and necessary to carry public confidence in many cases.

Adult fostering

Many people in prison are vulnerable adults, who failed to cope outside and whose vulnerability is often made worse in a prison environment.

This includes people with learning difficulties, mental health problems and poor life skills. It also includes people without family support (e.g. 1 in 4 prisoners have been in public care as children). However, many of these prisoners are a real social nuisance and /or at risk of harming themselves.

Partly for punishment and partly for want of anywhere else to send them, they end up in prison to be housed and supervised. An alternative approach in such cases would be adult fostering schemes, where they live with and are closely supervised by a family, in a similar way to children being fostered under state supervision up to the age of 18. For example, the UK has an NGO called Shared Lives, offering 12,000 vulnerable adults a foster home. This concept could be extended to take people on sentence, with many of the conditions outlined in the Home Arrest option (e.g. curfews and staying off drugs) but housing them with a supportive, well-trained and well-paid family.

This would still be cheaper than prison. One option is for the foster parents to have full parental / guardian rights (irrespective of the age of the offender) and control the offender’s money and key life decisions during the sentence. They should also have the right to recommend that an un-cooperative offender goes to prison.

Flexi-Prison

Sending people to prison full-time deprives many of them of their jobs, their marriages or relationships, their homes, their family/social structure and their income.

On the one hand that is what makes it a punishment. On the other hand, the things which are lost are the things which prevent reoffending. A balance could be struck if prison was part-time for some people. This could allow people to both lose what is important to them and their future, for part of the time, and to keep it too, for the other part.

A part-time sentence might, for example, require that over a 12 month period the offender serves 100 days (24 hours long) in prison, equivalent to most weekends plus annual leave from a job. Or it might stipulate that every weekend and 1 named night each week are spent in prison. Or that people need to find a job that works at weekends and attend prison during the week. Some people, if they can plan it and give enough notice, may be able to arrange things so they can manage a 60 day stint in one go, without losing their home or job.

Japanese Hogo-shi

One of the biggest problems about prison is that it takes, mostly, socially excluded people and excludes them even further from society.

Hardly anybody from mainstream society visits or engages with prisoners. There is a lot to learn from the Japanese system of probation (Hogo-shi). Unlike Western countries, 98% of the State’s 49,000 probation officers are volunteers. They have the status of part-time but unpaid civil servants. They supervise and give support to 40,000 offenders on parole and probation. They mostly use their own homes to meet the offenders. They commit to working with the offender’s family, help them find jobs and make social connections. Post-prison Hogo-shi halves re-offending rates. I think this would be a great idea for non-custodial sentences in other countries. But we could take this idea a step further.

Whenever a person is sentenced to prison, part of the sentence could be that they accept the supervision and support of a volunteer probation officer. The prisoner could be required to meet the volunteer prison officer at least once a week and they could enjoy visiting and communication rights similar to a lawyer. The volunteer probation officer could be a formal part of any decision-making about the prisoner (e.g. education, therapy, moving prison, internal sanctions, parole, exit plans, etc).

Critically, part of the sentence would be to fully co-operate with the volunteer probation officer for a defined period after leaving prison (e.g. 12 months) and for the volunteer to play an active role in helping the prisoner get a job, a home, stay clean, sort out any benefits and keep out-of-trouble. Like other probation officers, they would have the right to take offenders back to court if they are breaching their sentences.

This would have the added benefit of opening-up prisons to the community and reconnecting the excluded with many privileged and compassionate individuals. If every prisoner had one volunteer probation officer, we would have some 60,000 new people involved in our criminal justice system.

New Psychiatric Prisons

We can’t get away from the problem that too many seriously mentally ill people end up in prison because there’s nothing better for them.

Mental health services are generally dreadful in most Western countries. But there is a particular problem about prisons. In the US, 40% of people with serious mental illnesses have been in jail at sometime. 20% of the US prison population at any one time has serious mental illness. Of this group, 90% have been in prison before and 31% have been in prison 10 times, or more.

Like other Western countries, the US radically reduced the institutionalisation of the mentally ill by closing hospitals. It reduced the number of psychiatric beds by half-a-million (90% reduction between 1955 and 2005, despite a rising population). Since then, the mentally ill prison population has increased by some 400,000. In the UK, there were 150,000 people living in 120 “Lunatic Asylums” in 1955. Today there are just 18,000 in-patient psychiatric beds in the NHS. That number is just half of what it was 20 years ago, and falling.

Meanwhile in the UK the prison population has quadrupled since 1955 and doubled even in the last 20 years. It’s contentious and speculative to say that most of those people in Western countries who would have been in mental institutions were just re-institutionalised into prisons. But clearly many were. And too many.

The bigger job is to fix mental health services in the community. But a part of that is create a large number of appropriate and dedicated custodial facilities for seriously ill people who have to be imprisoned, but who are highly vulnerable, often terrified and in need of treatment. Such institutions need to find appropriate ways to punish as well as to treat and to care, but putting such ill people in a general prison environment is a disgrace.

Hard Labour

Prison and labour were for a long time seen to be a combined package when people were sent to prison. But the West’s use of labour for prisoners has declined.

During the 19th century, prison labour was mostly designed to be pointless. This included: turning a crank handle thousands of time in silence every day, moving cannonballs from one spot to another or powering a treadmill with one’s feet. In both cases, the labour achieved nothing. Convict labour gangs were widely used in the Southern USA, but too often looked like a new form of slavery to remain acceptable. In the 20th Century, some prisons have had useful voluntary labour, e.g. sewing mailbags or creating licence plates. There are some really inspiring work programmes, e.g. the Timpson’s scheme in the UK to train prisoners to be cobblers with the promise of a job when released. But forced labour for prisoners has disappeared from Western jails.

Unpaid work in the community as an alternative to prison has struggled to convince the public that it’s a serious punishment. Unpaid, hard, mandatory and purposeful work needs to be built back into prison sentences and to remain a commitment when offenders are released under licence. Civil libertarians hate forced labour. But it would mean that prisoners were unlocked from their cells, usefully occupied and, where it makes sense, taken out into the community to do the work.

Work is good for mental and physical fitness. And a good preparation for life outside prison. But where will the work come from? One solution would be to place a statutory duty on local government to create sufficient forced labour schemes and to use online voting locally to allow local people to choose what work they most want from their prisoners. This can be white collar as well as blue collar work. And if local businesses benefit from the work done, good luck to them, so long as the public backed the option.

Illustration of the 4th Circle (Greed) of Dante’s Inferno – by Gustave Doré (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

If prison is the only remaining serious punishment, we do need to re-imagine how we use it.

Hopefully, my options will stimulate people to think of better ones. Alternatively, those more imaginative than me might come up with a totally new punishment that strikes the right balance between public retribution and the dignity of the offender.

In Dante’s inferno, the nine circles of Hell include unique punishment for each sort of sin: e.g. pushing boulders (for hoarders); being immersed in human excrement (for flatterers); wearing a cloak of lead (for hypocrites); being permanently lodged headfirst in a block of ice (for betrayers of family); or, being chased and bitten by reptiles (thieves). But in our real world, the options may be more limited.

This article has been repurposed from Paul Kirby’s blog and is reprinted in full with permission from the author