A new report by the Children’s Society on behalf of Public Health England highlights the relationship between sexual exploitation and drug use.

Like their adult counterparts, young people in specialist drug treatment have a range of complex problems that extend beyond drug use. The latest treatment data from England reveal that 38% of young people (anyone under the age of 18) had at least 4 problems such as mental health, sexual exploitation or were affected by someone else’s drug use.

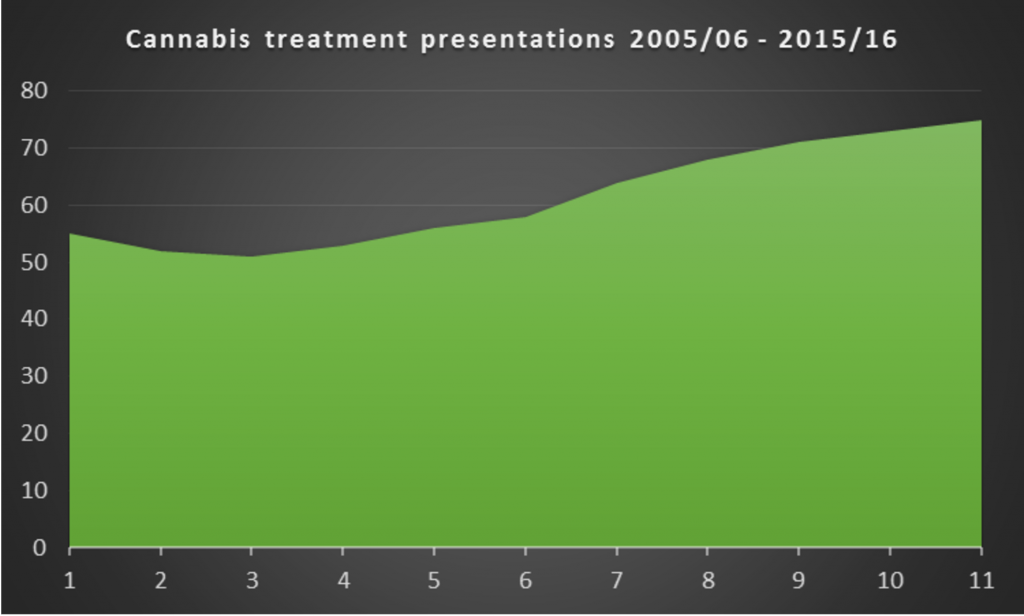

So, while the use of alcohol and drugs has been steadily falling among young people in general, more young people are presenting to treatment services with problems related to cannabis. A proportion of young people in treatment for cannabis accounted for 55% back in 2005/06, but this has since risen to 75% in 2015/16, and, when taking into account adjunctive drug use this number rises to 87%. This presents an interesting challenge as problematic cannabis use interventions are in an evidence free zone. With a lack of research as to what actually works, treatment providers are left in the less than ideal situation of having to fend for themselves.

The illicit cannabis market: a gateway to exploitation?

The report draws attention to the links between drug use and sexual exploitation, defining the relationship as:

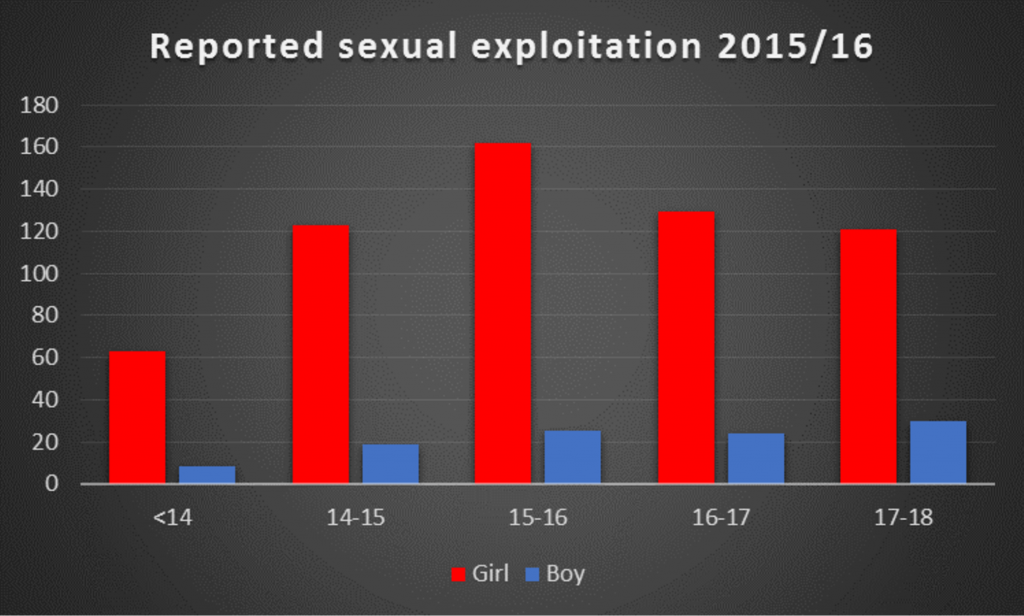

Sexual exploitation of children and young people under 18 involves exploitative situations, contexts and relationships where young people (or a third person or persons) receive ‘something’ (e.g. food, accommodation, drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, affection, gifts, money) as a result of performing, and/or another or others performing on them, sexual activities.

With problematic cannabis use identified as the primary issue for the majority of these young people in treatment there is thus a clear relationship between the two issues. Cannabis is serving as either a way of coping with trauma, or as an enticement into inappropriate sexual activity.

Although the data suggest that it is young females who are mainly at risk, Barnardo’s (among others) have warned that young men are less likely to report sexual exploitation.

We don’t know what proportion of young people who have a problem with drugs actually make it into specialist treatment services. Estimates for adult treatment suggest it as a few as 1 in 10. On that basis 170,000 young people could require treatment, a figure which would almost match the current adult drug treatment population.

The Great Divide

Reducing the barriers preventing children and young people from accessing appropriate support and services has been identified as a critical issue by the Department of Health. Improving access to effective support for mental health issues and in particular addressing the needs of the most vulnerable young people, such as those who have been abused or exploited, have been developed as key themes in a report developed by the Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Taskforce.

The report is clear about the consequences of treating children and young people’s specific health issues separately as this, they argue, fails to tackle the ‘overall wellbeing of this generation of young people’. A ‘needs led’ approach offering an integrated/interagency response is suggested as one of the ways in which these children’s needs might be addressed.

Mental health and problem drug use are closely linked but unfortunately mental health and drug treatment services are not. So while each of these complex young people present as a whole, the current service configuration responds by partitioning their various problems to specialist providers.

The majority of young people are referred into specialist drug treatment by their school or youth justice. With only 4% of referrals instigated by child and adolescent mental health services. The Children’s Society found systemic barriers to multi-agency working:

Substance misuse professionals reported difficulties in supporting young people to access Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), primarily because either young people did not meet the access thresholds or because they were not stable enough to engage in CAMHS treatment.

Joining dots and banging heads

In a recent survey conducted by the children’s charity Barnardo’s, 7 out of 10 children aged 11-15 said that they felt they should receive sex and relationship education in school. The report stated that sex and relationship education was ‘unfit for the smartphone generation’ of children who are exposed to the internet and influenced by social media.

This is a view echoed by charity Young Minds, which has identified concerns from young people regarding sexuality and relationships. Their campaign calls for a revitalised sex education programme in schools which would give young people opportunities to talk about their concerns, and help them develop their understanding about healthy relationships, consent, how to stay safe and where to access online support for concerns and worries.

Some joined up thinking is required between government departments. But by blocking plans to make sex and relationship education compulsory in schools the government has thwarted one important way in which school aged children could learn about exploitation and how to deal with it.

Compounding this is the manner in which the current regulation of drugs interferes with the ability of services to provide balanced and credible information to young people. ‘Talk to Frank’ offers state sponsored propaganda which focuses on risk and harm, with no mention of the pleasures and benefits of drug use. If this is your first experience of public health information it could tarnish your view of any further messages.

Public Health England have subcontracted the Talk to Frank initiative to Serco, however, this doesn’t look like good value for money as they have managed one tweet in five years (!).

Evaluation of the Frank initiative is difficult to find, the last review conducted by Addaction in 2008 found that only 1 in 10 young people would be willing to call its helpline.

Commissioners of drug treatment have a critical role to play, they can ensure that providers attend to the link between exploitation and problem drug use in young people. Equally they must ensure that there are clear transition arrangements from young people to adult treatment services, ideally via the same service provider. At a point in their lives when continuity matters most, being passed from young people services to adult drug treatment services is not the way to nurture and maintain trust.

By default or design the current system of care for these young people is fractured, disconnected and complex, paradoxically reflecting what these young people themselves are often experiencing.

Ian Hamilton is a lecturer in mental health in the Department of Health Sciences at the University of York, with an interest in the relationship between substance use and mental health (Dual Diagnosis). Tweets @Ian_Hamilton_

Alison Smalley is a lecturer in Mental Health Nursing at the University of York, who also is a specialist in mental health issues concerning young people.