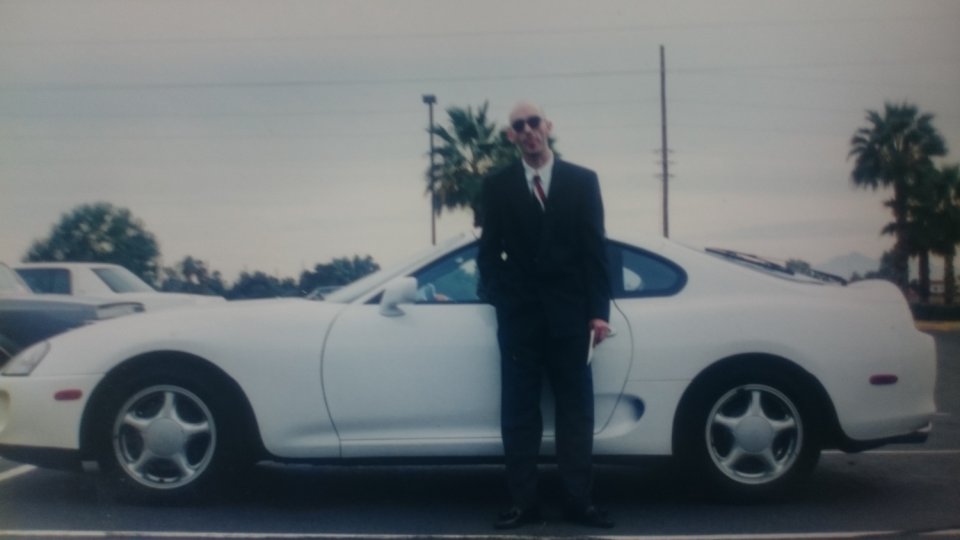

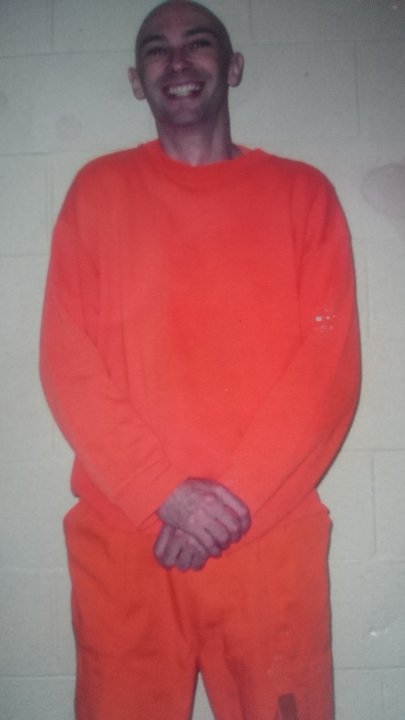

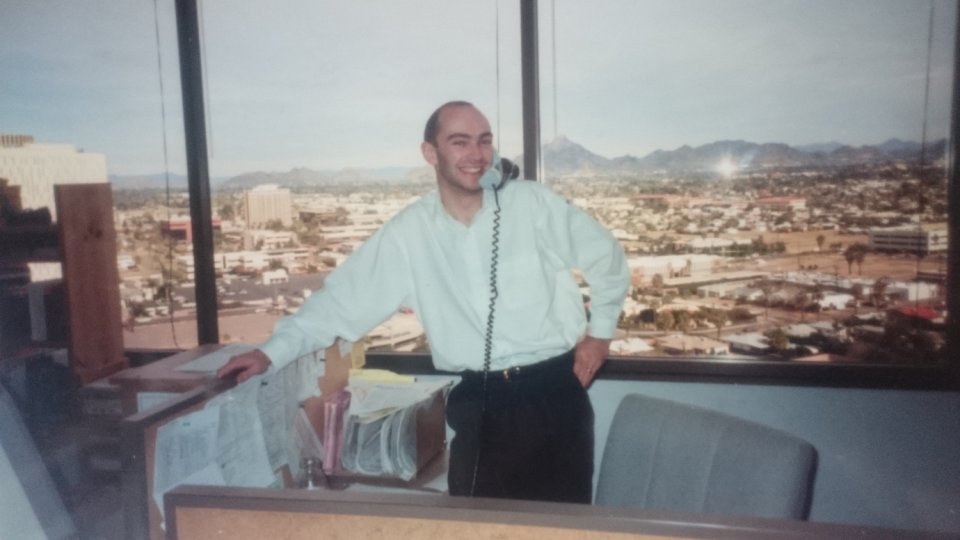

After a successful career as a stockbroker in Arizona, Widnes-born Shaun Attwood experienced even more success as a major Ecstasy distributor. However, it all came crashing down after Attwood was caught and sentenced to 9 and a half years in Arizona’s state prison.

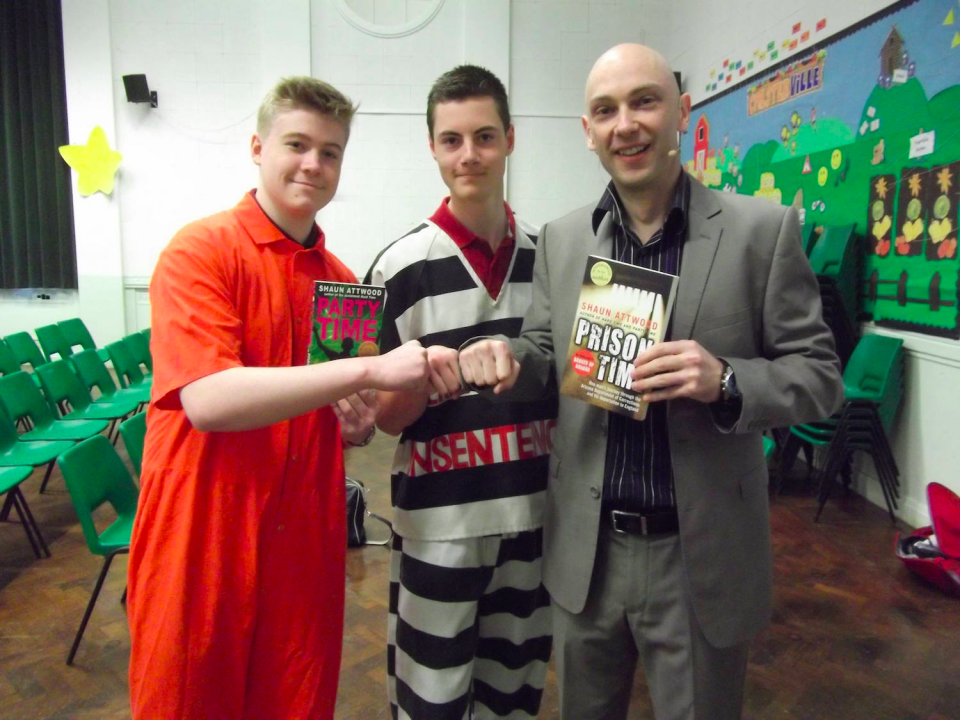

Whilst incarcerated, Attwood began to keep a diary, which was smuggled out and typed up online by his relatives and visitors. The result was Jon’s Jail Journal, a blog where Attwood could share his eye-opening tales of life on the inside, documenting the brutal conditions he experienced in jail. The journal’s popularity earned Attwood a book deal upon his release: the ‘English Shaun’ trilogy, wherein Attwood shared his remarkable life story. In addition to becoming an author, Attwood has also devoted himself to educating and informing young people, racking up over one hundred talks at schools across the United Kingdom.

VolteFace spoke to Attwood about his work as an advocate for prison reform, and, how closely connected the dire state of contemporary prisons are to the misguided ‘War on Drugs’.

VolteFace: You have a new book out – ‘Pablo Escobar: Beyond Narcos’ – what attracted you to Pablo Escobar’s story?

Shaun Attwood: It’s a long story! About 5 years ago I did a talk at a school in Woking. A student saw my talk and was inspired to study Criminology at Winchester University. As a thank-you-gift she sent me a copy of Johann Hari’s book ‘Chasing The Scream’. There’s some mutual inspiration going on there as Johann had read my book ‘Hard Time’ as part of his research.

Meanwhile, I had been researching the ‘War on Drugs’ for years – reading and listening to audio books and Youtube videos as I drove around the country going from talk to talk. It felt like a natural progression forward from the subjects of my previous books: a prison reform activist exposing the War on Drugs. The War on Drugs is, of course, responsible for a great deal of the profiteering and other terrible issues affecting prisons in the US.

So I had all this research building up, and I particularly enjoyed how Hari’s book brought together lots of different figures whose lives inter-weaved. I wanted to write a book that did something similar and would show how the lives of lots of different characters overlapped. So I started to write that book, and then I saw Narcos, and having done so much research on Escobar I thought I might as well just write a whole book devoted solely to him, and make it part of a trilogy which would bring in all the other characters.

It’s going to be a ‘War on Drugs’ trilogy: the 2nd instalment will be about Barry Seal [drug smuggler and pilot], and the 3rd will simply be called ‘We Are Being Lied To: The War on Drugs’ revisiting the project’s original premise.

What are your thoughts on the popularity of programmes such as Narcos, Breaking Bad, and Broadwalk Empire (to name only a few) that portray the lives of drug lords?

‘True Crime’ has always been a big genre, and they are just parlaying that interest into these dramas. But they are sacrificing the truth – for example: Pablo’s story typically involves ‘badass’ special forces who are supposed to represent ‘the good guys’ vs ‘evil drug lords’ who represent the forces of evil, when the actual situation (in Colombia) is far more complex than that.

You have credited reading as the most valuable thing you did while incarcerated. How important are books and reading for prisoners?

Reading was the lifeblood of my rehabilitation. I had addiction issues and I didn’t understand that I had been self-medicating with street drugs and by reading philosophy and psychology texts, they forced me to look inside myself and address the root causes of my addiction, and do all of the inner work that was necessary, and build up tools so that, when I got out, I wouldn’t be drawn to that addictive behaviour. My experience in prison was, therefore, the education opportunity of a lifetime!

Do you feel that US prisons are experiencing the same problems that those in the UK are with drugs?

A: Yes. The bottom line is, if you look at the figures – the most arrests in the US (at the time I was arrested) were for cannabis. If you look at the drug use arrests against what was being taken in prison then: young people come in and they graduate to heroin, they graduate to crystal meth. 90 percent of the prisoners I was housed with were shooting up heroin and/or crystal meth. A great deal of them got Hepatitis C from sharing dodgy needles.

Why do you think so many prisoners start shooting up? How did you avoid it yourself?

Hari’s book talks about the Rat Park experiment – where researchers put rats in cages and rats who could get recreation, run around outside, and offered them either water or water laced with heroin. The rats who couldn’t get outside of their cage would, time and time again, get hooked on the heroin -laced water.

If you put people in an environment where the people treat you like animals, where the threat of violence makes you feel continually under stress every day, where you aren’t getting sunshine, you aren’t getting proper food – then your stress goes through the roof. When I first got to prison I couldn’t sleep for the first few days because my heart was beating out of my chest. So people, especially people dealing with the stress of a long sentence, turn to the hardest drugs possible so they don’t have to deal with it and get out of their minds.

In Arizona there was no attempt to rehabilitate prisoners at all. The guards were selling drugs to prisoners – it only takes one or two guards to flood the whole prison. Drug laws have corrupted everything – they have corrupted the police, the prisons, the prison guards – it’s inescapable.

What is your perspective on drug laws in the UK at the moment? It appears as if, in absence of a strong government lead on drug policy, the police are only selectively enforcing the law..

Well, it is what happens when you base laws on moral relativism, as opposed to – if you look at why prisons were created in the first place, it was to stop people from hurting each other – crime had been defined by murder, rape, robbery etc, however, in the last hundred years you have these statutory drug laws, which are laws that govern people’s behaviour so you have people drinking alcohol, popping prescription pills, saying “you guys who smoke weed are evil and must be incarcerated for it to save your own souls!” It’s completely arbitrary.

It comes back to your questions about heroin – in the UK and US, prison rules and procedures are used as a carrot and a stick to govern behaviour. If a guard doesn’t like a prisoner, they will threaten them with a urine test, knowing full well that prisoner will test positive for heroin or something else and they will lose their privileges. So because of that, heroin, and now spice, which are harder to test for then cannabis. The testing incentivises harder drug use, because those drugs stay in the system for a much shorter time.

I spoke at HMP Thameside recently, and that was flooded with ‘spice’ and I am getting letters from prisoners I knew in Arizona who are telling me that their prison is flooded with spice as well now.

How can people working in Drug and Prison policy improve their way of communicating with the public, who are largely unaware of just how dire the actual scenario in prisons is?

In America it has changed slowly because so many people were arrested for weed, and there was a backlash against criminalisation at the state level. When you have a kid calling home saying ‘Mum, I just got caught with some pot, I’m in prison with a cellmate who has a padlock in a sock who is threatening to rape me. I need ten thousand dollars to get out on bail, I need a lawyer. That’s when people start to wake up. And the federal government has cannabis set as a schedule one substance, but people at the state level have gone against that, demanding reclassification for medicinal cannabis. So in terms of cannabis, there has been a change of heart, and even people like Hilary Clinton now are saying that they will take cannabis down to schedule two, riding that wave of popular opinion.

With heroin, there is a popular opinion that users are causing crime, shoplifting, robbing houses etc. However, in my home town – Widnes – in the late 80s I think, where they ran a pilot scheme to provide heroin to addicts, crime stats collapsed. We had shops putting up money to keep the program going, and there were plans to roll it out nationally. The DEA got wind of it, and there was a call to Downing Street and the whole thing got closed down.

From your experiences travelling around the country, doing a hundred talks a year, what do you find people are most interested in asking you about?

I mostly speak to students in years 10-11, and college kids. I’ve noticed, which is very hopeful, as so many young people nowadays are accessing information online, is that a lot of them are hip to the War on Drugs and are, as a result, turning against what the government are saying about drugs. I think it is all going to add up in the long run.

Lastly, could you tell us a little bit about your meditation practice?

One of the things I teach to schools are ‘life lessons’, and one of these lessons is – learn a relaxation technique. From my own experience, I had tried to deal with all the built up stress from my days as a stockbroker with drugs, and obviously that lead to various self-destructive ups and downs. When I got to prison, dealing with the awful conditions, facing a 200 year maximum sentence, it became like a vice that forced me towards meditation. At first it was impossible to slow down my thoughts, as prison conditions were so hectic. However…

You can buy Shaun Attwood’s books online.

Words and Interview by Calum Armstrong tweets @vf_calum