Yesterday The Times published an op-ed response to The Tide Effect report released by VolteFace and the Adam Smith Institute on Monday by columnist Alice Thomson. The report argues that the only way to bring cannabis under control is to legally regulate it. Thomson presents the counterexample of Colorado, the US state where cannabis has been legal longer than any other, and paints a bleak picture of the place since the change. Her article plays on the understandable fears of many regarding the impact of a regulated market by sporadically drawing what seem to be very credible and alarming statistics.

Thomson makes a number of serious claims about the consequences of cannabis legalisation in Colorado, including data in relation to seemingly dramatically increasing road accidents and crime rates.

This new public debate about how best to manage the demand and supply is an important one. It is vital that it is conducted honestly and openly. The veracity of the evidence used by reformers and those in favour of the status quo should be unimpeachable.

Thomson’s rushed response fails in this regard. Almost all of her claims are misleading, many are products of national trends across the US and others represent a fundamental misrepresentation or misunderstanding of the available data.

This joint response by VolteFace and the Adam Smith Institute to Thomson’s article draws on the rich and varied evaluative data that has been produced from an array of creditable sources since Colorado implemented the policy of legalising and regulating cannabis sales in 2014.

Road deaths have increased by 48 per cent in the past two years

This figure contradicts official data from Colorado’s Department of Transport for both Denver and Colorado as a whole. In Denver, 50 people have died in road accidents in 2016 so far, and 52 died in 2015. This is up from 43 deaths in 2014 and 40 in 2013 – a much smaller percentage increase than Thomson claims.

In Colorado in general, road deaths are up, but again by nothing like 48 percent – 492 deaths in 2016 and 507 in 2015 up from 451 in 2014 and 431 in 2013. The report Thomson cites, produced by the Rocky Mountains High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (we’ll get on to them later), which has slightly different figures, still only shows a 14 percent rise in road deaths, from 481 in 2013 to 547 in 2015, much smaller than Thomson claims though still significant.

But is this effect specific to Colorado, and so possibly caused by its cannabis legalisation? No. The US as a whole experienced the largest rise in traffic fatalities in 2015 for fifty years – up 8% nationwide.

This effect was not evenly distributed around the country report the National Safety Council: “Oregon (27%), Georgia (22%), Florida (18%), and South Carolina (16%) all experienced increases in fatalities.” Oregon’s law legalising recreational cannabis only came into effect in October 2015, and none of the others have recreational cannabis laws, so cannabis cannot be to blame.

So what is the cause? According the the NSC: “While many factors likely contributed to the fatality increase, a stronger economy and lower unemployment rates are likely at the core of the trend.” Not legalised cannabis.

the American Automobile Association [found] that twice as many fatal crashes now involve drivers with THC, the main psychoactive constituent of marijuana, in their system.

Actually, the report Thomson is referring to is about Washington state, not Colorado. And if Thomson had read that report she would have seen that it explicitly states that its results “do not indicate that drivers with detectable THC in their blood at the time of the crash were necessarily impaired by THC or that they were at-fault for the crash”. Indeed of the drivers involved only one-third were not also under the influence of alcohol or other, illegal, drugs.

In Colorado, the number of fatalities in accidents with drivers testing positive for cannabis rose from 71 in 2013 to 115 in 2015, but this does not imply that the cannabis caused the crash, or that cannabis was responsible for an overall rise in fatalities.

More rigorous research looking into the impact of medical cannabis laws shows that legalisation reduces traffic fatalities by 9 percent thanks to the substitution effect – in short, people driving under the influence of cannabis instead of more-dangerous alcohol.

Hospital visits linked to marijuana use have increased by 49 per cent

Hospital visits linked to cannabis have indeed increased since the change in legislation, with a report by the Colorado Department of Public Safety listing hospital visits linked to cannabis between the 2010-2013 period at 1440 per 100,000 visits, while in the 2014-2015 period, this figure rose to 2413. The report urged caution in interpreting the data however, stating that it should be considered “baseline data because much of the information is available only through 2014, and data sources vary considerably in terms of what exists historically.”

In fact it goes on to provide some explanation for the marked increases in figures: “Legalization may result in reports of increased use, when it may actually be a function of the decreased stigma and legal consequences regarding use rather than actual changes in use patterns. Likewise, those reporting to poison control, emergency departments, or hospitals may feel more comfortable discussing their recent use or abuse of marijuana for purposes of treatment. The impact from reduced stigma and legal consequences makes certain trends difficult to assess and will require additional time to measure post‐legalization.”

Colorado doctors have also pointed out that measures defining a hospital visit as cannabis-related are also often “arbitrary”, being based on medical codes that make “any mention of marijuana”, and being “assigned by billers, not practitioners at the bedside”.

the murder rate has risen 15 per cent.

Once again, Thomson has arrived at this impressive-sounding figure by ignoring national effects and not looking at the numbers in absolute terms.

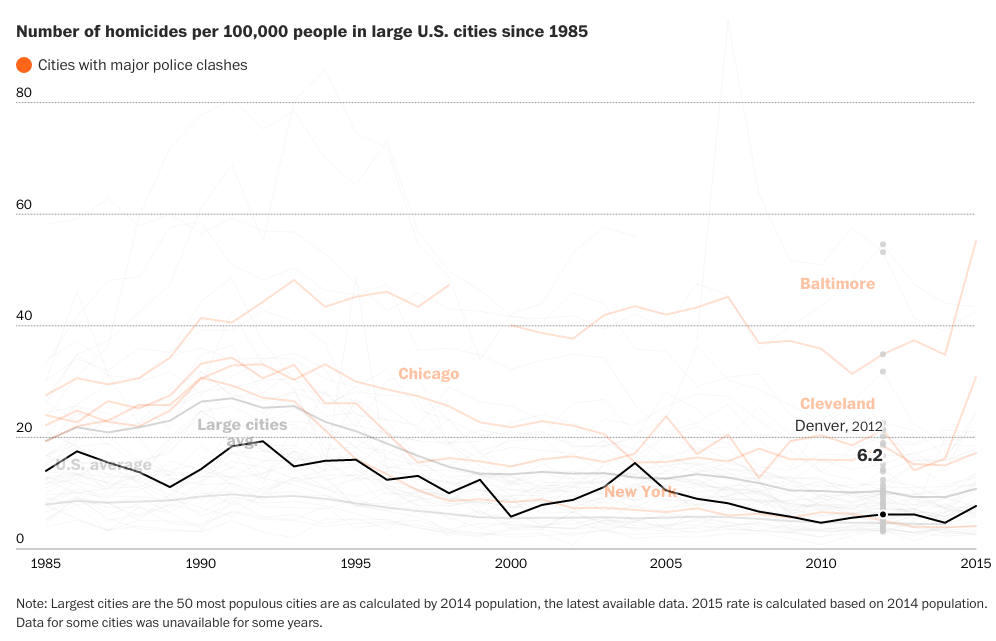

Across the United States, the murder rate rose by 10.8 percent in 2015, an effect driven by large rises in murders in American cities where there was a 15% rise.

Obviously, a rise in murders in Chicago or Baltimore cannot be blamed on Colorado’s cannabis laws, and a rise in murders in Denver may also be driven by the factors affecting those cities. The Colorado Bureau of Investigations’ crime report made no mention of cannabis as a factor affecting the homicide rate there.

But Thomson’s numbers actually seem to understate the rise – different sources suggest that Denver’s murder rate has risen by between 36% and 65%.

Why might that be? Because if we look at the absolute numbers of homicides rather than just rates of change, Denver is a very safe place overall. In 2014 there were just 31 murders in total in Denver, according to the Denver Police Department, which rose in 2015 to 42 and in 2016 to 48. So this effect was driven by an extra eleven murders – in other words, quite possibly random noise.

Even after these rises, Denver’s murder rate is now only at the level it was in 2006, and is lower than almost every year before that. The Denver Post notes that the city’s “projected 2015 murder rate was lower than average among the nation’s 30 largest cities”. The graph below shows Denver’s murder rate compared to other major US cities.

Theft and burglaries are on the increase and the number of criminal prosecutions has grown by 44 per cent.

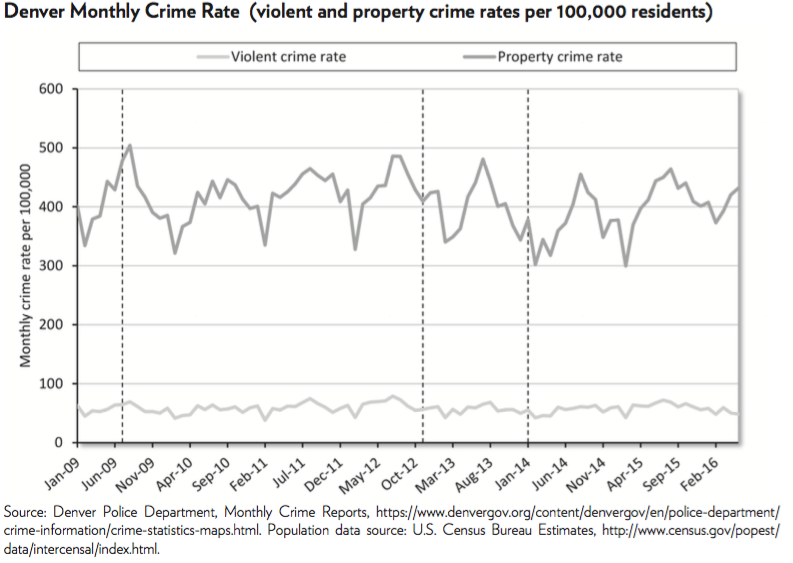

Here again is a serious case of misrepresentation of the actual crime rates of Denver/Colorado, omitting to take into account both the population growth of the state, the second highest in the US, and the wider patterns of crime seen across the US. Thomson’s 44 percent increase, taken from a report by RMHIDTA, is at odds with figures from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report, which show an increase of only 3.5 percent over the same period. Corrected for population growth, neither the violent or property crime rates for Denver show any increase, as the graph below shows:

Denver police spokesman Sonny Jackson is quoted as saying “Crime is up, but I don’t know if you can relate it to marijuana.” This is the conclusion also reached by a study conducted by the Metropolitan State University of Denver.

The number of children using dope has also spiralled

In fact, teenage use of cannabis has fallen mildly since legalisation, according to Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment, to a level slightly below the national average. The RMHIDTA, presumably Thomson’s source for this statement, suggest otherwise however.

a third more (children) are now excluded from school

This is an error based on a misreading of the source, or a reliance on second-hand sources. A third more students have not been excluded from school – drug-related suspensions and expulsions have risen by a third, according to the RMHIDTA. A much much smaller number.

Data from the Colorado Department of Education actually finds the reverse trend to the RMHIDTA, with the number of drug-related expulsions showing a steady decrease since legalisation, numbering 718 in the school year ending in 2012, falling to 614 in 2013, 535 in 2014, 446 in 2015 and to 337 in 2016, of which 195 were cannabis-related, the 2016 being first year where such a distinction was made.

38 children under the age of five were hospitalised last year after accidentally consuming the drug

This alarming figure comes again from the RMHIDTA, the data originating first from the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center. Unfortunately it’s not true. There were 38 calls to the RMPDC that mentioned cannabis exposure in children 0-5 years old in 2015, which tallies with similar statistics reported to the Colorado Department of Public Safety. This is in itself a concerning issue, but again a partial explanation for the increase can be found in the decreased stigma that has accompanied legalisation emboldening those calling in to the RMPDC to mention cannabis.

A phone call to a poison centre involving mention of exposure to cannabis is very different – and far less extreme – than a hospitalisation. Lack of clarity in the RMHIDTA report and failure to check the original source are to blame, helped by a willingness to jump to the most dramatic explanation. Underage cannabis-related hopitalisations in Colorado have increased since legalisation, but by no means to the same extent that Thomson implies, and the extent of the increase must be kept in context – it is still minor in absolute terms.

What’s more, the predicted fall in alcohol consumption has not materialised.

Thomson’s source for this is unclear as she does not provide figures herself, but if it is the RMHIDTA report she has used elsewhere, it presents figures from the Colorado Department of Revenue for Colorado for Liquor Excise Taxes to show an increase in alcohol consumption from 2011 to 2014 of 4 percent across the state. The report itself offers these numbers as proof of the same point Thomson makes.

What it does not mention is that the population of the state rose by nearly 5 percent during the same period, according to the US Census Bureau. This indicates that during that time, alcohol consumption per Coloradan at most stayed constant, or actually decreased. Factor in the increasing rates of tourism seen during the period, which would also account for increases in alcohol consumption across the state, and it does appear that Coloradans are drinking less.

Far from leading to a peaceful, over-the-counter trade, legalisation has triggered a 99 per cent increase in illegal distribution of the drug as gangs try to avoid paying tax.

Here again, Thomson’s numbers, orginating first in the same RMHIDTA report, is at odds with those of the Colorado Department of Public Safety report, quoting data from the Colorado State Judicial Branch, which notes a general reduction in distribution offences from 2011 to 2015 of 23 percent (304 to 235).

The DA believes that police are now busier investigating marijuana-related crime “than at any time in the city’s history”.

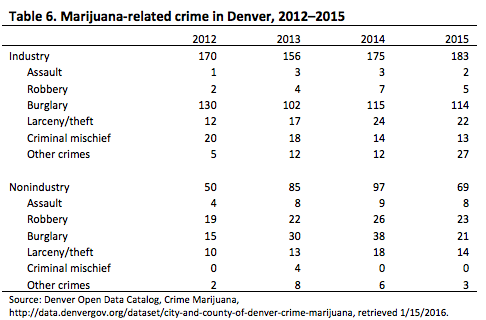

Despite this assertion by the DA, cannabis-related crime in Denver has not shown a major overall increase since 2012, according to figures reported by the Colorado Deportment of Public Safety, detailed in the table below.

When normalised for the increase in the population of Denver during the period, this indicates that cannabis-related crimes have not increased per capita.

They would want to advertise, introduce better packaging and provide more choice with cannabis shakes, smoothies and cookies, as they do in Denver. Cannabis would inevitably become easier for children as well as adults to access.

We agree with Thomson here with her first point, in fact we make it ourselves in Chapter 6 of our report. We don’t, however, make the leap of faith needed for her second, as it misses out the crucial point at the heart of The Tide Effect, which is that the best protection for children comes from effective policy and regulation, rather than prohibition. Long term downward trends in underage alcohol and tobacco consumption indicate the UK is more than capable of enforcing such measures.

By now, a trend in Thomson’s sources may be starting to emerge – the majority of her figures originate from a report produced by the RMHIDTA. But many of their figures are found to be either in disagreement with official figures from several different Colorado state departments, including Transport, Education, Public Safety, and Public Health and Environment, or a misrepresentation of their statistics to give a negative impression of legalisation.

Whereas the Colorado State Department attempts to communicate the data without agenda and provide tentative qualification for any trends seen, the RMHIDTA do not, and have in the past been shown to doctor data to suit their agenda. This is perhaps unsurprising for an organisation that, though supposedly neutral, has the explicit purpose of reducing cannabis production and distribution. Without further investigation of the RMHIDA’s sources, this would lead any reader directly to the same doom-laden conclusions about legalisation that Thomson herself arrives at.

Thomson appears not to have looked at her sources, because she makes several important errors. She cites a study about Washington state in a discussion about Colorado, which itself is explicit that it does not show that cannabis use was the cause of the crash, she mistakes a rise in drug-caused suspensions and expulsions with a rise in total expulsions, and mistakes phone calls for hospitalisations. More broadly, by not reporting the complex factors contributing to, say, hospital visit data, putting data such as crime statistics in the context of national trends or normalising for population changes, Thomson misrepresents the data continually to produce an oversimplified and completely untrue image of the consequences of cannabis legalisation in Colorado.

Thomson’s argument that the status quo be maintained is an honest one but it is dishonestly made. There is still much we need to understand about the impact of legally regulating cannabis markets but one-eyed responses underpinned by shoddy evidence serves no one well as this debate become more mainstream.

Henry Fisher is the Policy Director at VolteFace. Tweets @_Hydrofluoric

Sam Bowman is the Executive Director at the Adam Smith Institute. Tweets @s8mb