Watching from the other side of the world as the stories of Alfie Dingley and Billy Caldwell unfold has brought a sense of déjà vu to many Australians. It is like an echo of recent events in Australia, which was itself an echo of events in the USA. The story goes something like this: a highly publicised case(s) focusing on the health of a child stonewalling from the government public pressure and grass roots advocacy capitulation review/discussion apparent ‘legalisation’ systemic problems with access reform.

Australia is crawling towards the end of that chain, hopefully resulting in a functional medical cannabis access system that balances compassionate access to products for those in need with a realistic appraisal of their therapeutic potential. It has been a difficult and protracted process with many dramas along the way. Perhaps our experience can help streamline the approach of other countries – such as the UK – as they go through the often fraught and contentious process of legalising medical cannabis.

Déjà vu all over again

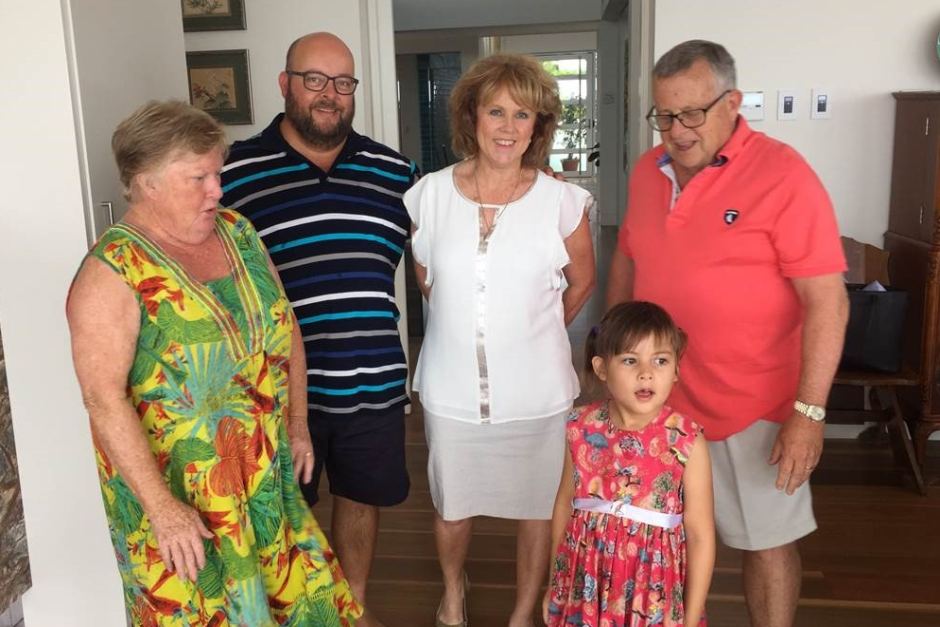

The Australian journey towards legalisation was never a proactive political agenda informed by the emerging medical science, rather it was a response to public pressure and overwhelming public support for medical cannabis. While the UK has Alfie and Billy, our own champions included Lucy Haslam, a woman from country Australia married to a former drug squad detective, whose son Dan could only find relief from his Stage 4 bowel cancer by smoking cannabis that his parents illegally sourced for him.

Lucy and Dan Haslam

Barry and Katelyn Lambert (right), Joy and Michael Haslam (mid)

The initial patient access framework that was put in place to respond to this pressure was bloated with committees, expert advisory boards and bureaucracy. It seemed almost guaranteed to ensure that access would not occur, with a whole raft of onerous requirements at both State and Federal government levels. After an initial year where only 300 patients received products, the scheme is now being significantly overhauled, and doctors around the country requesting a medical cannabis prescription will soon only be required to complete a single online form with most applications assessed within 48 hours. This is exactly the sort of reasonable policy that should have been implemented back in October 2016 when applications first started being accepted. Unfortunately, it took many months of community activism, intense media criticism, and a lot of unnecessary pain and suffering, to get us there.

What not to do

Unlike other countries, such as Canada, Australia attempted to legalise medical cannabis by incorporating it into our existing regulatory system for pharmaceutical products. The stated intention was to treat cannabis like any other drug and leave it up to doctors to decide when it was appropriate to prescribe. The reality has been perversely different.

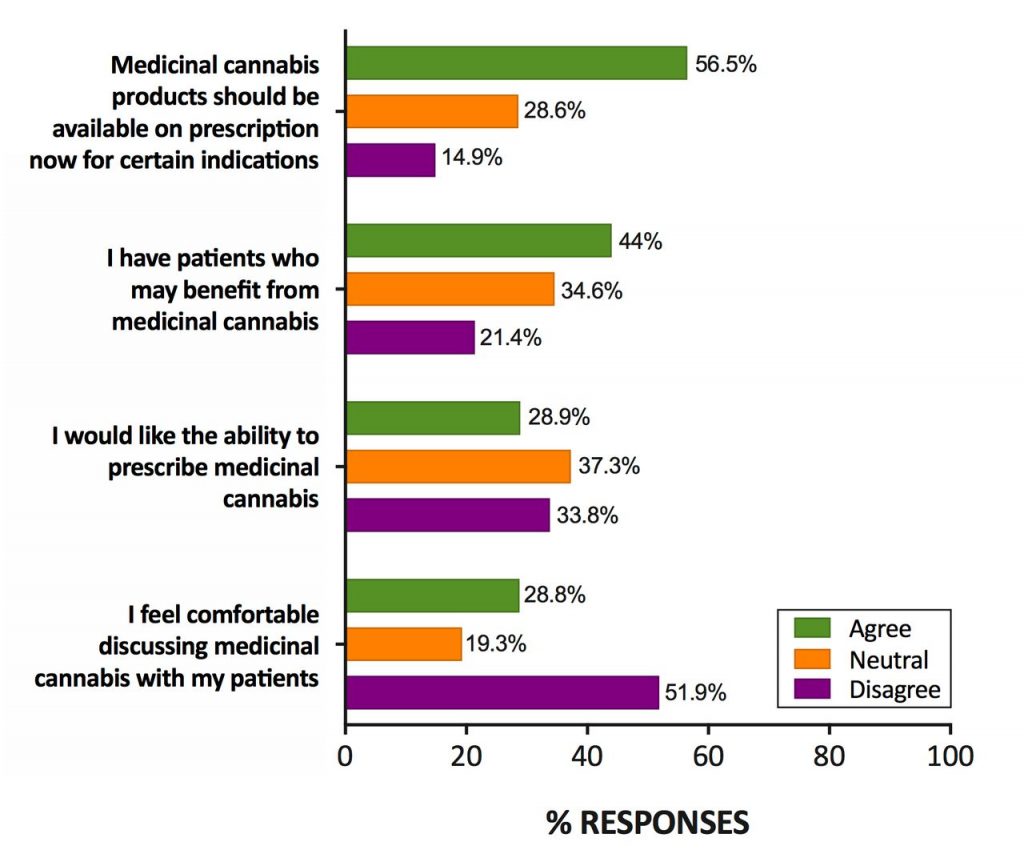

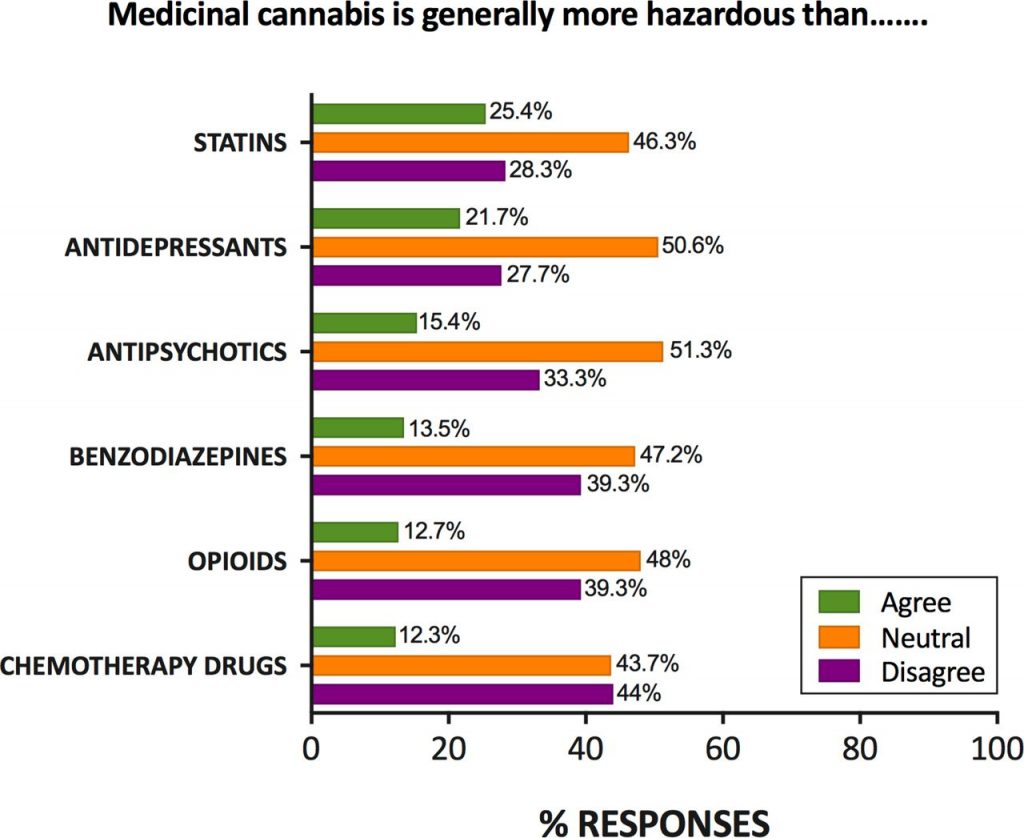

Even without specialist training, most general practitioners (in Australia at least) support the prescription of medical cannabis and know that it is probably less harmful than mainstream prescription drugs such as opioids and benzodiazepines. However, they feel inadequately educated around both its therapeutic and potential adverse effects, making discussions with patients uncomfortable.

In contrast to Australia, the Canadian system means that doctors don’t have to stand in the way of reasonable patient access while they become experienced in its clinical use. This is particularly important for cannabis-based medicines. With more than 100 potentially therapeutically active ingredients, available in a near infinite number of combinations and concentrations, it is impractical in the extreme to wait for a century of missed scientific research to be conducted before allowing access. Especially since illicit cannabis is already widely available and used.

In Australia, a doctor needs to make a detailed application to the Federal Department of Health specifying the clinical history of the patient; demonstrating they have exhausted all other available therapies; explaining the medical scientific literature they have researched that supports their clinical decision to try a cannabinoid therapy; specify and justify the exact product, dose and treatment regime being requested; and – most of the time – the doctor in question must be a specialist physician, not a general practitioner. Thankfully, once our new national framework is fully implemented later this year, doctors will no longer have to submit additional, even more cumbersome, applications to their State or Territory Health Departments.

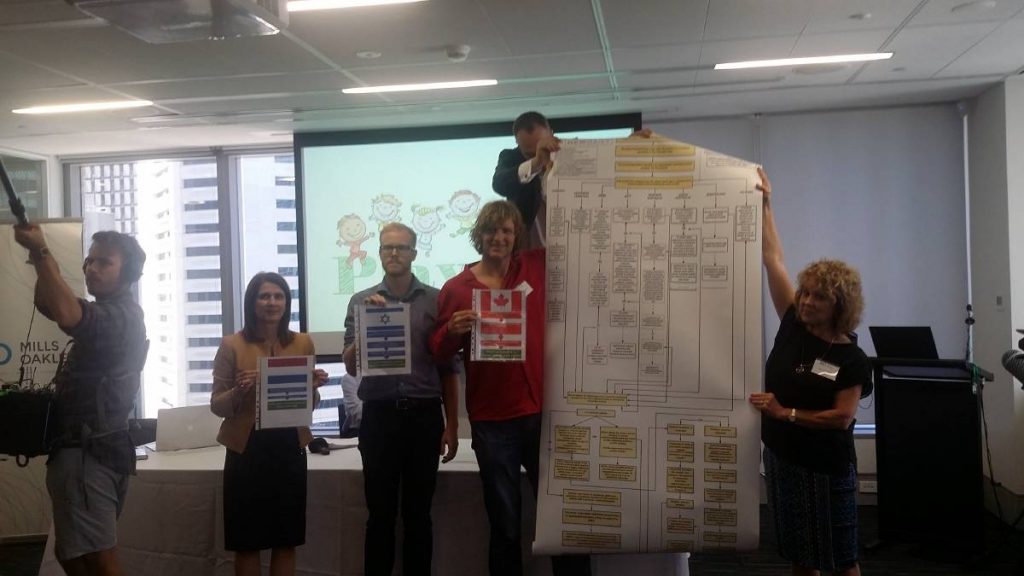

Lucy Haslam comparing Australia’s patient access process

Some would argue that the Australian framework has been a total failure. But an assessment of any policy can only be done with reference to specific objectives and outcomes. The simplest metric would be the number of patients legally accessing a medical cannabis product. Given Australia has managed to provide legal access to around 1,000 people in two years, while an estimated 100,000 patients continue to self-medicate with illicit products, a positive assessment on the basis of “number serviced” seems unlikely. But this would imply the objective of the framework is to provide access to as many people as possible, which is not the case.

The balancing act

There is a trade-off to be made between managing potential harms to those who need medical cannabis and preventing harms to those who do not need medical cannabis. Determining who needs medical cannabis is not always easy but there are a few circumstances where we know the net clinical benefit is likely to be positive: palliative care; chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; intractable epilepsy; MS spasticity; and chronic pain. That list will continue to grow as scientific research and clinical trials rapidly accumulates new evidence for specific cannabinoid preparations in treating specific conditions.

An assessment of any medical cannabis framework should be based on how reasonably this trade-off is managed. Are there circumstances where people who probably should be given access to medical cannabis are being blocked? And are there circumstances where medical cannabis is being provided in a way that is harmful?

The potential risk of doctor overprescribing needs to be managed. This is done with other drugs vastly more addictive and dangerous than cannabis and should not present a problem to any sophisticated health regulator.

The potential risk of illicit ‘diversion’, where medical products reach recreational users, should also be managed. But in Australia, around 10% of the country use illicit cannabis every year. Cannabis is both easy to access and cheap to purchase, with street cannabis containing very high levels of THC and almost no CBD. Medical cannabis oil with low levels of THC that is prescribed to someone in palliative care, or to a child with severe epilepsy, is not likely to be diverted or abused. Especially since legal medical cannabis is extraordinarily more expensive than street cannabis. And if it were diverted, it would be a drop in the ocean of illicit cannabis already available.

1200 cannabis plants seized by Australian police in March 2018

Price is not a trivial issue. Australia’s physical distance from established markets in Europe and Canada, our still nascent local industry, our stringent safety and quality standards for medicines, and an ongoing lack of policy leadership, mean those lucky enough to get a medical cannabis prescription can often ill afford it. For children with severe epilepsy, a years’ worth of medicine could easily cost AUD $60,000. Whereas many are already accessing illicit cannabis oils from community suppliers at a fraction of that price.

But the most serious risk to the healthy functioning of any medical cannabis framework is putting doctors in the driving seat before the pedals are installed. A framework that relies entirely on the initiative of doctors to educate and train themselves, to navigate an unwieldy bureaucracy themselves, to be solely responsible for all the concomitant moral and legal obligations, without providing significant support and instruction, is doomed to fail. And people will suffer as a result, both patients and doctors.