Colorado’s judiciary are having a busy time of it right now. From Nelson v. Colorado, the Supreme Court case that will decide whether the state’s Exoneration Act of 2013 violates the right of its citizens to be presumed innocent until proven guilty, to the decision – made by voters – not to remove language from a state law that allows “involuntary servitude” (i.e slavery) as a punishment for a crime.

But one law change in particular – or rather, a combination of two – has caused quite the uproar among the Centennial State’s burgeoning cannabis community. Initiative 300, a ballot initiative that proposed the creation of a four-year pilot programme allowing bars and restaurants in Denver to create designated marijuana smoking areas outside their establishments, was approved by the city’s voters on November 8th. The new law means that businesses can apply for a city-issued “consumption area” permit, provided they have the backing of a local neighbourhood or business group.

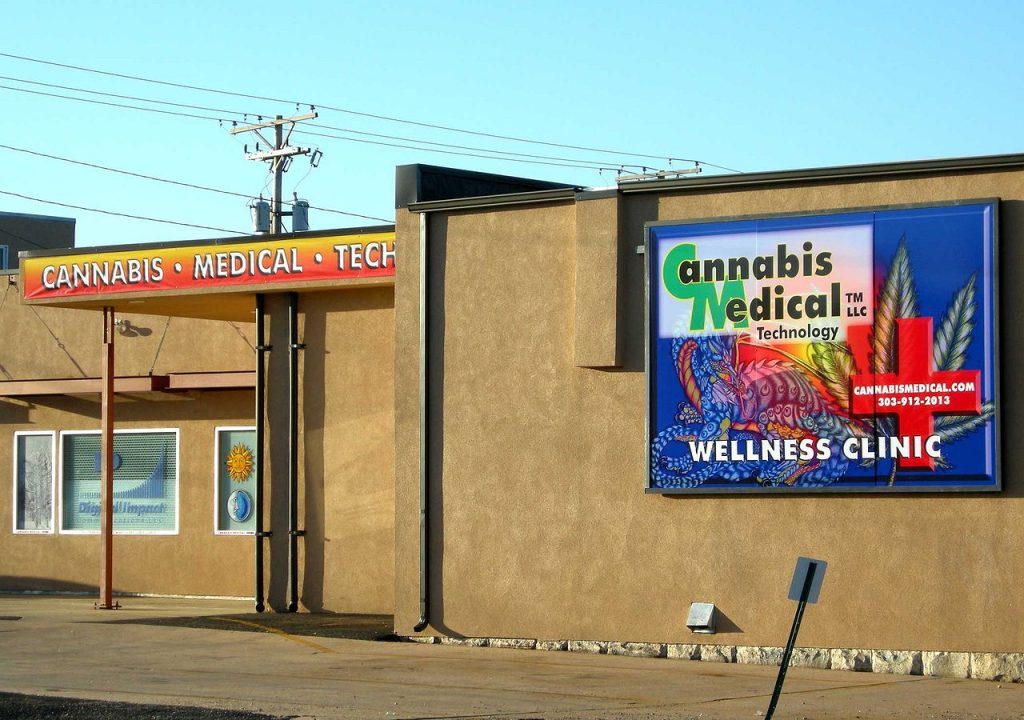

The thinking behind this move was eminently sensible – up until it passed, there was almost nowhere for cannabis consumers to meet up, socialise, and consume their favoured herb, despite the fact that Colorado legalised four years ago. Technically there were cannabis social clubs in Denver, but many of those were operating outside of the law, and were not exactly easy to find. Opening social consumption up to bars and restaurants was seen as a great way of fixing the issue, bringing the operators of illegal clubs into the fold, and providing somewhere for Denver’s many cannabis tourists to enjoy themselves safely. It seemed like a win-win situation, and voters agreed.

City Hall, however, were unconvinced. Less than two weeks after the vote, state licensing authorities issued a press release announcing a new law: bars and restaurants that already hold a liquor license will not be eligible for the new cannabis permit.

Restricting the scope of Initiative 300, the authorities claim, is necessary to protect public health, but legalisation advocates are far from happy. The decision came after the Colorado Department of Revenue held talks with the liquor industry, health experts, and groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, leading many to claim that the new policy, far from being in the public interest, is in fact simply pandering to outside interests who stand to lose out once cannabis consumption becomes more mainstream.

“They seem to think it’s fine for patrons of bars and concert venues to get blackout drunk, but unacceptable for them to use a far less harmful substance like marijuana instead,” Mason Tvert, spokesman for the National Marijuana Policy Project, told the Los Angeles Times. “This rule will not prevent bar-goers from consuming marijuana, but it will ensure that they consume it outside in the alley or on the street rather than inside of a private establishment.”

Whatever the reasons may be for implementing this new policy, what is clear is that Colorado is still at the forefront of cannabis policy reform. Their experimentations are paving the way for the latest raft of pot-legal states to follow in their footsteps. Californian lawmakers, for example, will be able to draw upon their Coloradan counterparts’ four years of experience in creating a safe, well-regulated, cannabis marketplace, now that they have finally legalised. The same goes for Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada.

The fact is that, thus far, no state has passed a perfect legalisation measure, and in all likelihood none will. Although it can seem at times like we’ve entered the endgame of the fight for legalisation, with more and more states and countries moving away from the tried and failed tactics of prohibition, the reality is that this is just the beginning. The trailblazers – Colorado, Oregon, Washington, etc – may have a few year’s head start on the rest, but even their markets are still very much in their infancy.

As a result, it is inevitable that cannabis policy will continue to evolve even where legal markets exist. As Brendan Kennedy, CEO of Privateer Holdings, pointed out during a debate hosted by VolteFace earlier this year, Colorado lawmakers have continually adapted and changed their cannabis regulations since 2012, at times on a weekly basis. So whilst the decision to exclude many of Denver’s bars and restaurants from inclusion in Initiative 300’s pilot programme may seem arbitrary and possibly even corrupt, it is by no means set in stone. Should the programme be a success – and there is little reason to think that it won’t be – it is perfectly possible that it would not only be extended to cover the whole state, but also those businesses that have been sidelined right now.

An example of why cannabis advocates should not despair just yet can be found in the ongoing disputes – in all legal states – over whether people with previous drug convictions can work in the legal cannabis market. Every state has implemented different rules. In Colorado, the law stipulates that any individual with a previous felony conviction be barred from owning a marijuana business for five years. Originally, if that felony happened to be drug-related, that went up to ten years. Convicted felons may still, in theory, hold an occupational license allowing them to work in the industry, but in practice (according to anecdotal evidence at least) applications for these licenses are declined more often than not.

This may not sound good, and indeed it isn’t, but already progress has been made in changing it. The length of time that drug felons are now barred from owning marijuana business has been cut to five years as of 2013, and the Licensing Authority “may grant a license to a person if the person has a state felony conviction based on possession or use of marijuana or marijuana concentrate that would not be a felony if the person were convicted of the offense on the date he or she applied.” Again, pressure and experience have forced change, and not just in Colorado.

Alaskan lawmakers announced draft legislation earlier this year that would have gone even further than Colorado in terms of restricting the ability of convicted felons to work in the industry. They proposed barring people from cannabis industry employment of any kind if they had a felony conviction in the last five years, had been convicted of selling alcohol without a license in the last five years, or had been convicted of a misdemeanour crime involving violence, weapons, dishonesty, or a controlled substance other than a Schedule VI controlled substance. The proposals drew huge criticisms from the industry and the public, who argued that they were deeply unfair and discriminatory, particularly as there are no such restrictions in place in the alcohol industry.

Thanks in large part to those criticisms, the Alaskan Marijuana Control Board voted at the end of October to remove the restrictions from the draft legislation. Background checks are still required, and there are still very strict rules on who can own a marijuana business, but if you want to get a job in an Alaskan dispensary, a major hurdle has just been removed.

The point I’m trying to make here is that rather than panicking whenever there’s a new regulation attached to a state’s legalisation measure that they don’t like, cannabis advocates are far better served by realising that legalisation is a process. Right now, Colorado and others are in the experimentation phase of that process, and there will be hiccups along the way. They’ll learn from others – like Alaska – just as much as others will learn from them.

As we saw in California during the run up to the US election, there are still many reformers who are resistant to change if that change is not, in their eyes, perfect. They tried (and thankfully didn’t succeed) to derail Prop 64 because they failed to realise that whilst the passing of the law may represent the end of one journey, it is also just the beginning of another. As more and more systems of regulation emerge, the best models will continue to be refined and the worst elements will be dropped. It’s going to take time for that process to come up with a ‘perfect’ system, and even then it’s likely that what works for one state, or country, may not work for another. Patience and determination will get us there, despair and rage at every small bump in the road will not.

Deej Sullivan is a journalist and campaigner. He regularly writes on drug policy for politics.co.uk, London Real, and many others, and is the Policy & Communications officer at Law Enforcement Against Prohibition UK. Tweets @sullivandeej