It’s safe to say that conferences devoted to talking about women and drugs are few and far between. Not because this is a niche area, indeed, 30% of the treatment population treatment are women (an underrepresentation of women who experience addiction), and 1 in 20 women in England and Wales took illegal drugs in 2015/16.

Nor is it because gender is irrelevant. Though we are all individuals, our lives are still embedded within a social context and gender is an integral part of that context. There are certain experiences that women are more likely to be familiar with and certain experiences that men are more likely to be familiar with. Frankly, when it comes to drugs – it seems gender hasn’t been given the attention it deserves.

But then, if gender is what we should be concerning ourselves with, why was this drugs conference only talking about women? As expected, there are the inevitable twitter trolls who surface when any kind of twitter hashtag focuses on women’s rights and needs. Although I would doubt that they are actually interested in drug addiction and treatment, it does open up the question, what about men? Though of course male experiences should not be ignored, there is evidence that drug treatment is largely used by men, geared towards men, and is therefore guilty of neglecting women’s needs.

Dr Emma Wincup, Senior Lecturer at the University of Leeds, kicked off the conference by offering a gendered reading of the 2010 Drug Strategy. Her research concluded that ‘the 2010 drug strategy is largely gender-blind: there are only fleeting references to transgender drug users and to drug use within pregnancy.’ Rather than recognising gender, the strategy prefers to simply talk of ‘individuals’. Yet there are some individuals (namely women), who are more likely to be the person who has parental responsibility for a child or who is within an abusive relationship, and these gendered differences will impact on the sort of support that is need.

Karen Biggs, CEO of Phoenix Futures, moved the conference onto a piece of research they had undertaken which examined the importance of motherhood. The research came out of the women who use Phoenix’s services highlighting that they felt motherhood was being neglected:

I have 2 kids, 1 is in care and 1 lives with his Dad. All through my treatment I’m asked loads of questions about myself and no one has asked me if I am a mum. They ask me if I have parental responsibility for any children which I don’t, so that makes me think they don’t think of me as a mum

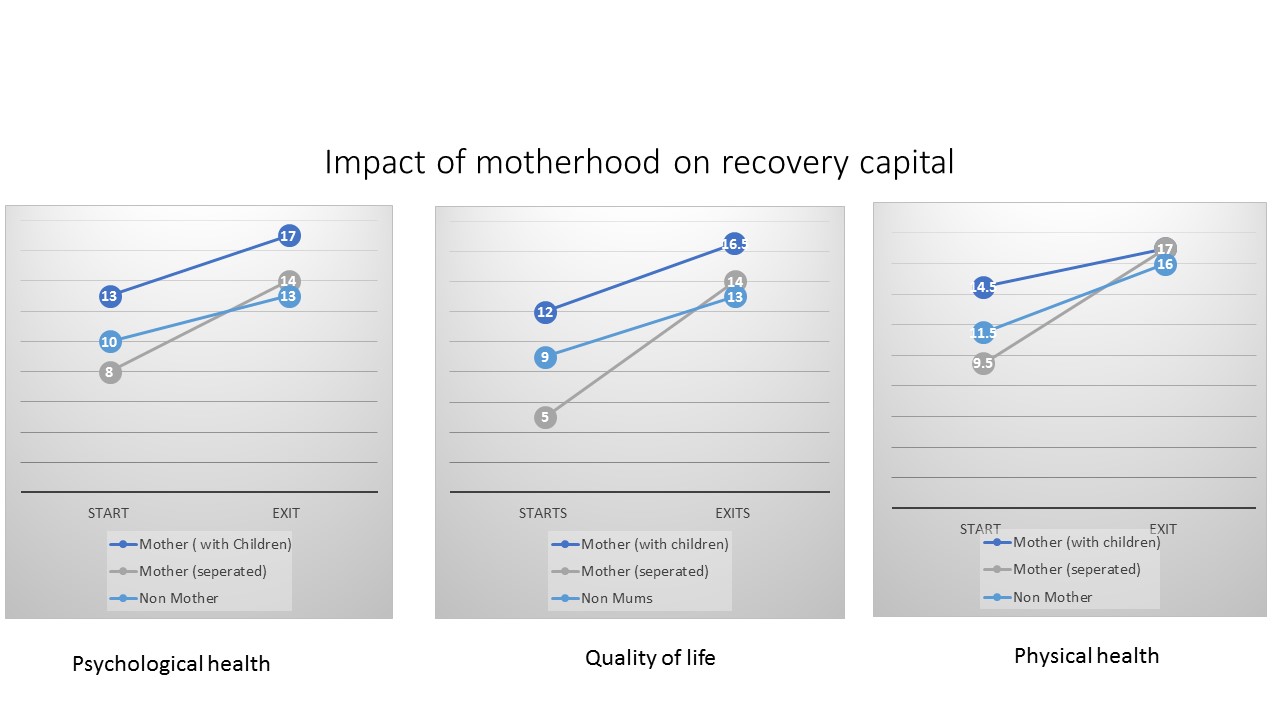

Phoenix’s study found that ‘motherhood acts as a differentiator in women’s access to and progress through treatment’. Using psychological health, physical health and quality as life as parameters, a mum who keeps their children starts and ends with the highest recovery capital, a mum separated from her children makes the fastest progress and a woman without children makes the slowest improvement.

(Image: Phoenix Futures)

Biggs concluded that ‘by understanding this we have been able to ensure our programmes respond more effectively to the needs of all women’.

Gail Gilchrist, a Senior Lecturer at KCL, drew focus to the fact that there are also certain risk factors that are more likely to occur among women who experience addiction, which include higher rates of childhood abuse, intimate partner violence (IPV) and mental health problems. Incidences of these risks among women who use substances are greater than among men who use substances and women in the general population. Gilchrist argues that to address these multiple disadvantages, services need to adopt ‘treatments that address problems more common to women, taking a gender sensitive approach. Integrated services that consider and address the relationship between substance use, mental health and inter-personal violence are urgently needed’.

(Photo: The Mental Elf)

Katherine Sacks-Jones, Director of Agenda, said services need to recognise why women use drugs to ensure they are receiving appropriate support and do not fall between the gaps of service provision. She explained “women with addictions very often have experienced violence and abuse which can be deeply traumatising and have long-lasting and profound impacts. Some women use alcohol or drugs as a way of coping and blocking out feelings and memories”.

Yet women find themselves between a rock and a hard place as:

[..] services set up for those with addictions tend to be largely used by men and rarely respond to the needs of women, including their experiences of abuse. On the other hand, services set up for women (such as domestic or sexual abuse services) often lack the capacity or specialist staff to support women facing addiction.

Women may be restricted from accessing refuges because of their drug use. Drug treatment can be accessed, but for women who have histories of abuse, a service which is composed of nearly 3/4 men can be threatening, frightening and sometimes unsafe, particularly if the service is used by current or previous perpetrators of abuse. There is also a problem of women feeling that they are being overly judged by services and staff, particularly if they are also involved in prostitution.

Jenny MacNeil, the Lead Recovery Clinician at York Hospital echoed these concerns of stigma by explaining that there are different expectations of women’s treatment journey, with some staff expressing dismay at slower recovery because they have a child. There are then further challenges for women to build trust with professionals as they are encouraged to be honest about their substance use but if they have parental responsibility, social services may be called and their child is taken away.

The conference then shifted to more everyday matters and the importance it plays in recovery. Professor Sarah Nettleton from the University of York argues that academic research which studies people who use heroin, typically focuses on deviance/acquisitive crime, needle sharing and blood borne viruses. However, Nettleton’s research indicated that it was far more mundane matters which were of more importance, with sleep emerging as a key issue. Nettleton’s interviews with women who use heroin concluded that ‘sleep is critical to the quality of women’s lives and yet access to good sleep is highly gendered; women experience more difficulties with sleep because they are more likely to be on low income, in insecure or no employment, have greater caring responsibilities and less able to access secure and safe environments for rest’. She concluded that solutions lie not in understanding the biological basis of sleep but the politics of place and ordering of social arrangements.

(Photo: The Mental Elf)

Professor Liz Hughes from the University of Huddersfield then moved the conversation onto the disadvantages women face in academia, particularly within the field of substance use. She explained there is roughly an even split of genders awarded a PhD but the Higher Education Statistics Agency reveals that women are severely under represented among Professors and within journals of addiction. Hughes argued that transparent recruitment and mentorship for postdoctorate early researchers would help to promote women in research and help combat the cultural and structural barriers as well as women’s own views, values and beliefs

The final presentation was a talk from lecturer and podcaster, Dr Suzi Gage, who discussed the methods for countering misinformation, one way was to make something yourself with Gage best known for her award-winning podcast ‘Say Why to Drugs’.

Finishing on a reflective tone, Gage questioned whether ‘Say Why to Drugs’ could do more to recognise gender:

Until this point, I haven’t really discussed gender during my podcasts. This conference really highlighted to me that this may be an oversight. Take, for example, the link between cannabis and psychosis – one of the largest studies on this topic was using conscript data, so based entirely on men. Public health recommendations for everyone are based on these kind of studies, so we could be missing important differences or distinctions.

Volteface too admits that it could give greater consideration to gender. Too often, it seems that talking about drugs implicitly means talking about men. This does not mean we shouldn’t be explicitly talking about men. If we are not to be gender blind, it is necessary and important to consider the social context that men are embedded within, how this could shape their relationship with drugs and what this means for women. For example, it is essential that motherhood is given adequate attention, but fatherhood should equally be part of the conversation, particularly as it is a role which is prone to being undervalued. This question is already being considered with Phoenix Futures stating that ‘our next task is to understand better the impact fatherhood has on development of recovery capital’.

Undoubtedly though, a conference about women and drugs was long overdue and hopefully won’t be the last. Though this year the focus was on addiction and treatment, in the future, Volteface would be interested in finding out more about women’s recreational relationship with drugs, particularly with the rising trends in women seeking emergency care after taking MDMA.

Lizzie McCulloch is a Policy Advisor at Volteface – read her report ‘Black Sheep: An Investigation into Existing Support for Problematic Cannabis Use’. Tweets @mccullochlizzie1