In the run-up to Lowlands last year, a Dutch festival with a lineup packed full of the likes of Tame Impala, New Order and Live Electronic Godfather Paul Kalkbrenner, Lara Smit visits the Jellinek drug-testing facility in Utrecht with a key question: Does Government Funded Drug-Testing in the Netherlands Prevent Deaths?

“If my daughter had been able to get her drugs tested, she might have still been alive today.”

Ever since ecstasy and MDMA gained popularity in the 1980’s, the Dutch have been able to get their drugs tested at government funded testing-facilities. But does the testing of illicit drugs prevent drug-related deaths?

She was only 15 when she died. Martha Fernback took half a gram of unusually pure MDMA in an Oxford park with a friend. Three hours later her mother, Anne-Marie Cockburn, got a phone call. Her daughter was in hospital, fighting for her life. Cockburn has been fighting for legalisation and regulation of drugs since. “Had my daughter had the opportunity to get her drugs tested, she would have been able to make an informed decision, rather than blindly taking it anyway with devastating consequences. The system should be something where there’s good information available, there should be an environment that doesn’t contain the stigma that it currently does.”

It’s summer 2019, a small GP-like waiting room is filled with millennials. The line reaches outside the room, all the way into the hallway. This is the Jellinek drug-testing facility in Utrecht. It’s the week before Lowlands, a big Dutch festival and these people are all here to get their drugs tested (for free) before they leave. The DIMS (Drugs Information and Monitoring System) has 33 facilities all over the country, where people can get their drugs checked, anonymously and without fear of prosecution.

The Netherlands is one of the very few forward thinking countries that provides government-funded drug checking. According to Laura Smit-Rigter, national coordinator of the DIMS, it’s a win-win situation: “There are two main reasons why we test drugs in the Netherlands. The first is to monitor the drug-market, so that we know what is going around in the country, what substances are being frequently used, detecting risky substances and being able to warn people in time. Secondly, there is the harm-reduction side, where we can educate users about the risks of certain kinds of drugs and how they can minimise those risks.”

The number of drug-related deaths per million inhabitants (according to the European Drug Report 2018) in the Netherlands is 19, whereas this figure is a lot higher in the UK at 70. Looking at these numbers, it’s possible to say that the testing of illicit drugs works, although we can’t be sure according to Smit-Rigter. “The registration of drug-related deaths is something we are working on right now. Not every person that dies has a toxicology report made up that can determine whether or not the death was drug-related. What we do know is that because we monitor the market very closely and thus have very good idea of what kind of drugs are going around, we’re able to respond very quickly when something life-threatening appears, like with the pink Superman pill.”

A good example of the ‘Red-Alert’, an alert that takes place to warn users of dangerous substances, is when back in 2014 a bright pink pill with the Superman logo was submitted to one of the testing facilities, the Netherlands Institute for Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos). The pill turned out to contain a high dose of PMMA (paramethoxymethamphetamine) and no MDMA, which it was sold as. The 175mg PMMA found in the pill was a lethal dose. The next day the DIMS commenced a Red-Alert campaign, sending out warnings to the Dutch public via news- and media-outlets and the Red-Alert app. Although there were no deaths recorded in the Netherlands, in the following weeks a number of people died in the UK after using this extremely dangerous pink pill.

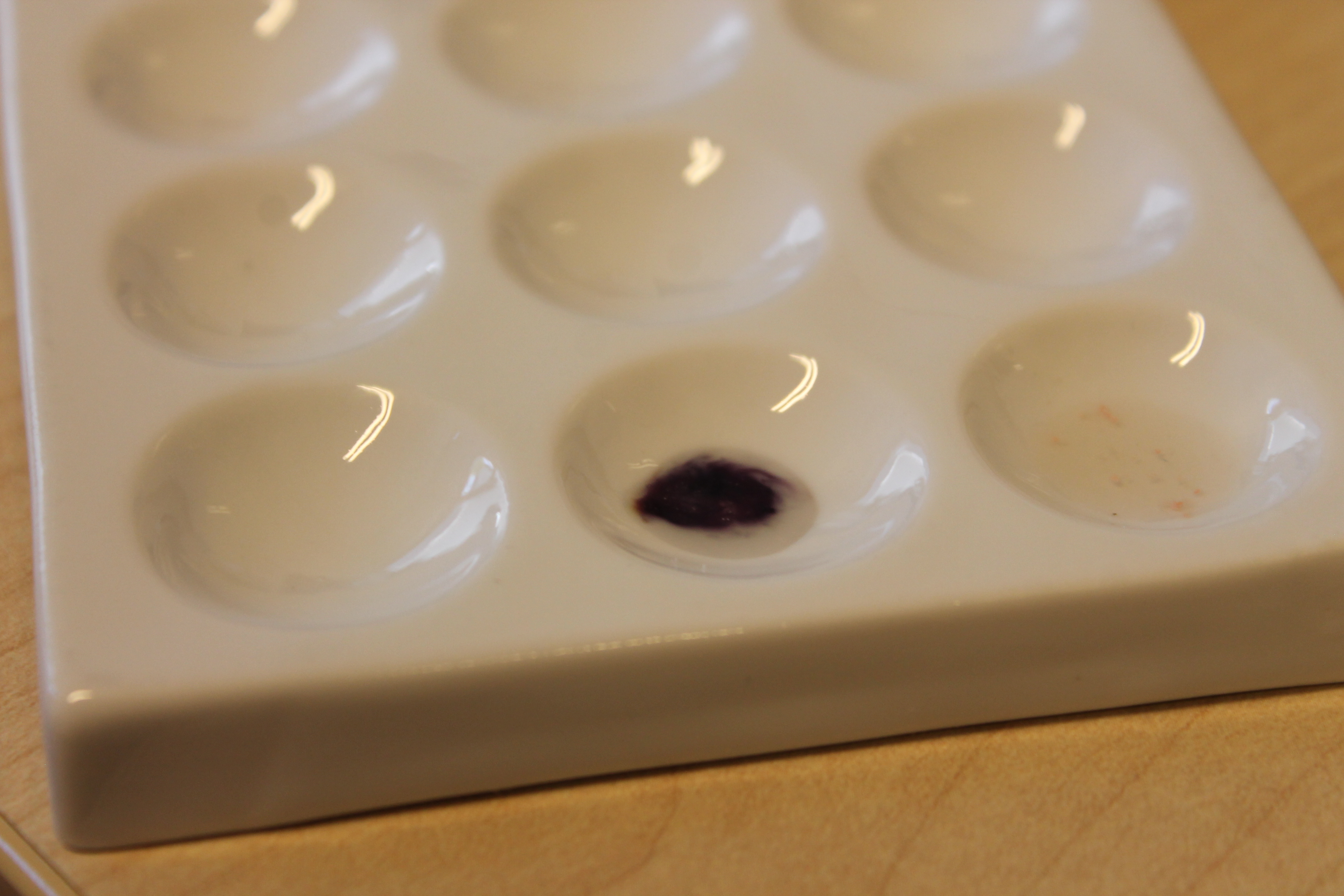

Left, the Marquis acid turns dark blue/black in reaction with MDMA. Right, the acid does not change colour with the scraping from alleged MDMA pill.

When visiting one of the testing-facilities in Haarlem, to see what the actual testing process is like, Marion Kooij who has been conducting drug-tests for over 20 years, takes a look at a pill that has been brought in the day before, sold as ecstasy. The 18-year-old that handed it in wrote down on the intake form that the reason for testing is because they don’t trust the dealer. It’s a peach coloured, round shaped pill debossed with ‘Q50’ on the side. After measuring the pill, she scrapes some of it off and adds Marquis acid, which reacts to the MDMA that should be in the pill. If the pill contains MDMA, the acid turns dark blue/black. Nothing happens, however. The acid remains transparent, so we can therefor conclude that the pill does not contain MDMA and is NOT ecstasy. After doing a bit of research online Kooij finds that the pill that has been handed in is actually Apo Quetiapine, a medication used for certain mental disorders like psychosis and bipolar disorder. “Well, there you have it. That is exactly why it’s important that we are here.”

Despite the public health benefits, not everyone agrees with government-funded drug checking. Simon Fritschij from Dutch political party ChristenUnie (Christian Union) thinks that it’s time to stop normalising drug use. “On a national holiday, like Kingsday in the Netherlands, people don’t find it weird to see people use drugs in the streets. I think that this partially has to do with how we look at drugs as a society. We, as a political party, want to move towards a drug-free society, although we are well aware that that’s not something you can’t fix within a few years. When we see the damage that drugs bring to our society, when we see how addictive it is, how much money is going around and how it doesn’t contribute to a healthy life, we want to move to a drug-free society. The first step would be to stop the normalisation of drugs. We think that drug-testing doesn’t fit in a society where drugs are illegal. Trying to discourage people to use drugs, while at the same time allowing to get them tested, is a very ambiguous policy. We need to be careful that we don’t create a false sense of security. With the way things are going right now, we give people the impression that when their pill has been tested, ‘it’s safe, it’s okay, have fun!’. In that sense we want a different kind of balance than there is now.”

Cockburn, however, doesn’t buy the normalisation argument.

“Normalisation is not a good argument against saving the life of a young person who is intent on taking a substance at a weekend or whatever. Regardless of your use and why, this is someone’s daughter or someone’s son and to me that is a precious life. That’s why it’s so important to keep this conversation going and showing them common sense.”

Ray Lakeman lost both of his sons, Jacques and Torin (aged 19 and 20), to an ecstasy overdose after they went to a football match in Manchester in 2014. He’s now a campaigner for ‘Anyone’s Child: Families for Safer Drug Control’, which is an international network of families campaigning to change current drug laws to be centred around honesty, compassion and health, instead of fear, discrimination and punishment. “After my boys died and I was talking to people that knew them, the thing that came through loud and clear to me, even though it was a very tragic event, was that they weren’t going to stop taking drugs. They just wanted to make sure that whatever they took was as safe as it could possibly be.”

Lakeman doesn’t think that testing normalises drug use, either. “Drug-testing is not condoning using it, it’s being pragmatic and accepting that that is what’s going on. Saving lives is more important than taking the high moral ground. Somebody dies and turning around saying ‘well, that just proves that drugs are dangerous’. It shouldn’t be that, it doesn’t need to be that way.”

That people are told that their drugs are ‘safe’ and okay to use, is actually not how it goes explains Smit-Rigter. “We are funded by the Ministry of Health, Wellbeing and Sports and their policy is that if you look at the big picture, you want to prevent people from using drugs, but for the people that decide to do them anyway, you need to minimise risk. We make sure that we tell people that drug-use is never without risk. When people visit the test-service we ask them why they are planning on using, for example. An important part of what we do is intervention and education. The test-service is completely anonymous. It’s very important that we have the users’ trust. We give them information and they do the same for us. If we break that trust, we won’t have a complete image of what is going on. It is that exact exchange of information and trust that gives you the right information to be able to prevent victims.”

Drug testing would be a good start, according to Lakeman. “I’m still finding it very hard to get my head around the fact that both my boys died of taking drugs, but the fact is that that is what happened, but how do we change it? If you could stop it, if you could ban it, then it would’ve happened years ago. People are always going to want to take drugs. You don’t want your own kids to do it, but if they are going to do it, then let’s make it as safe as possible. If that involves testing, that is a start. At least it’s testing what they taking and that reduces the chances of either overdosing or taking something which wasn’t what they thought it was and possibly keeping them alive.”

Cockburn took a very different route than people would have expected from her as a mother that lost a child to drugs. “Had I engaged with what Martha was doing, I wouldn’t be having this discussion with you. I could’ve kept her very well-informed, she could have made a decision that would have kept her safe, rather than going in to the danger zone, which is what she did. It’s better that you equip them with the information that they need for what they’re going to do anyway. Because if you don’t educate them, they’re going to take risks. To me it’s no different than teaching your child how to cross the road safely or putting a seatbelt on when you’re in the car. It’s all about safety. I wish I’d had a very different discussion with Martha and I’ll always regret not knowing how to respond to what she was doing, because my response was very old-fashioned and it wasn’t realistic. I wasn’t listening to her, I was just terrified of how laid back she was about what she was doing. So I shouted at her to stop, I didn’t want to hear it and a few weeks later she never came home and that was it. That could have been a very different conversation.”

Lara Smit is a freelance journalist and be contacted at contactlarasmit@gmail.com